The American Oriental Engineering and Construction Company was a building products supplier of sorts founded in Seoul in the early 1910s. Its arrival coincided with several important market changes, namely the growth of Christian mission station projects and the growing construction demands of an increasingly urbanized Korean peninsula. It also notably emerged in the wake of Korea’s annexation by Japan. All known evidence of the company points to its establishment being rooted in the work of Charles Loeber (1878-?), an American missionary from North Adams, Massachusetts.1 And while little is known of Loeber, remaining consular, missionary, and commercial records offer a glimpse into his life in Korea – and into his work with the American Oriental Engineering and Construction Company [AOEC].

Loeber was a student in the college of Liberal Arts at Syracuse University from 1904-1908, with university records suggesting interest in Christian foreign mission work. The annals imply he may have been in some position of leadership when he “outlined the missionary study work for the year” in a meeting on October 16, 1907.2 He was also reportedly to become the chairman of the YMCA missionary committee there the following year.3 The Massachusetts native was a member of the graduating class of 1909, yet he didn’t complete his studies. Instead, he and his wife sailed for Korea.

Their reason for departing at the time they did remains unclear, but the timeline has the appearance of being somewhat hurried. Not only did Loeber quit his studies at Syracuse relatively close to graduating, but he joined and trialed as a first year member of the Methodists’ Troy Conference in the spring of 1908. The Troy Conference’s minutes show Loeber was made a missionary deacon and elder on April 18, 1908, and subsequently transferred from the Troy Conference to the Methodists’ Korea Conference on April 20th. 4 The Christian Advocate then reported the Loebers sailing from San Francisco on May 9.5 In a statement years later, Loeber mentioned he signed his contract with the foreign mission board of the Methodist Episcopal Church in April 1908. It seems likely it was this contract that pushed the Loebers through the process so quickly.6 According to Loeber’s own account, they arrived in Korea at the very end of June.7

Loeber’s Work With The Methodist Mission

The Loebers were first stationed at Chemulpo, and while they seem to have maintained a postal address there for at least a year, they also moved around to different cities.8 Mrs. Loeber, whose full name remains unknown, was likely also engaged in missionary work alongside her husband. A resident of New York, she studied at the YWCA Training School and had some experience in the Hospital Training School for Nurses at North Adams, Massachusetts.9 They might have worked in Chemulpo for about a year before being reassigned.

No known records offer any suggestion as to why Loeber became involved in construction work as a missionary. His home life prior to university remains a mystery and his being a liberal arts student does not seem to indicate any particular interest in engineering or the sciences. However, by the spring of 1909, Loeber was reportedly reassigned to the mission at Yeng Byen [Shinuiju, northern Korea], being referred to as a “Student of Language and Assistant in the Construction of Mission Buildings”.10 He became attached to the Methodists’ Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society [WFMS], which had a growing presence in Korea, and was dubbed a superintendent of some of their building matters, possibly at Yeng Byen but it seems he also was involved in other buildings. One publication mentions he was in charge of plumbing a (presumably Methodist) hospital at Pyongyang, and another source noted he was involved in the work for the Methodist hospital outside the east gate at Seoul.11 A later statement indicated that Loeber was specially appointed to this position and that he was involved in building matters from 1908-1910.12 He then appears to have abruptly submitted his resignation to the mission as trouble arose.

It was early 1910 when Loeber officially closed his time with the Methodist mission. He gave notice in January, with his resignation taking effect at the end of April.13 The minutes from the Methodists’ Korea Conference in May 1910 confirm this as his trial period with them was discontinued, and The Christian Advocate reported in the following month that his resignation had been received.14 Shortly afterwards, it seems his financial accounting of building materials was called into question, and it was that summer that he was taken to court at the American Consulate-General in Seoul, overseen by consul general George H. Scidmore. The remaining documents from these proceedings are now the most significant block of materials informing the world today of the person that was Charles Loeber.

Arbitration Between Loeber and the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society

The accounting issue officially became a civil case lasting from 1910-1912, yet inaccessible remaining consular documents may suggest this accounting issue could have begun as early as 1909.15 The parties involved were also heard and several individuals made appearances. There was Merriman Colbert Harris, the missionary bishop overseeing the Methodist Episcopal Church’s matters in Japan and Korea, Lulu E. Frey, the treasurer of the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society [WFMS], Otto G. Foelker, who was Loeber’s attorney, and a W. A. Noble, who appeared on behalf of the WFMS. Dalzell Adelbert Bunker, who was serving as the treasurer of the Methodist Episcopal Church’s foreign mission board, is recorded as being the one who brought the case against Loeber.16

On August 5th, 1910, the American vice consul general Gould sent a letter to Loeber, summoning him to appear in court six days later at the Consulate-General in Seoul. The letter directed Loeber to bring a defense for (1) why the court should not order a full account of his dealings with the Methodist mission, (2) why the court should not order Loeber pay the foreign mission board anything he may owe, and (3) why “general relief” and the costs of the legal proceedings should not be placed upon Loeber. Bunker and Loeber appeared at the Consulate-General on August 11th, at which time statements were taken and Loeber asked for postponement of further proceedings in order to secure an attorney, the aforementioned Foelker, from New York.17

Bunker’s statements show he took issue with Loeber’s accounting while working for the mission, particularly since there were certain records Loeber wouldn’t provide. One of the documents produced was a letter Bunker had written to Loeber dating to June 16, 1910, in which he demanded “a complete set of books of accounts, vouchers, receipts, and bills, covering all all [sic] transactions while you were in the employ of the [foreign mission] Board.” Bunker continued his demands for records of any profits, receipts, and expenditures of “any business” Loeber was involved with, and finally demanded “an accounting of all transactions of all mission money or property”.18 In addition to Bunker’s financial concerns, he also thought Loeber was doing what researcher Dae Young Ryu described, based on missionary letters, as “private business with parties outside the mission with mission funds.”19 Bunker specifically stated Loeber had undertaken some kind of private work for Dr. William Benton Scranton, claiming it was outside of the Methodist missionary’s contract.20

All of this appears to have been born of an audit of Loeber’s accounts that began on June 2, 1910. In a report dating to June 23, which was submitted as evidence in these court proceedings, the auditing committee of the WFMS found all of the funds Loeber received from the WFMS in Korea while working for the mission were accounted for. At their request, Loeber also provided his accounts since January 1, 1910. However, there was apparently mission money that passed through his personal account with the Syracuse Trust Co., and the supplies purchased with this money were things he refused to offer records for as they were “in books which Mr. Loeber stated are his personal account books.”21 The auditing committee claimed to have found a 2016.303 yen discrepency that could not be accounted for without Loeber’s personal records. The committee also claimed they had found “irregularities” that past audits had missed. This is despite a memo, provided to the court, written by Methodist auditors in the U.S. claiming Loeber’s accounts were in order up until December 31, 1909.22 Lastly, there was the issue of what the committee claimed was Loeber’s acknowledgement of having “disposed” of 1200 yen worth of building hardware to “parties outside the Mission.”23 Loeber also refused to provide invoices or records of “hardware” matters despite stating he had them on hand, according to the report.24

Loeber’s statement in court on August 11th, 1910, contradicted Bunker’s claim that he was working outside of the mission, stating he only did work for the mission and that the work he did was within the bounds of his contract with the Methodist mission.25 The documents he later provided to the court indicate he had been working directly with the Methodists’ foreign mission board in the United States, and confirm that they had been directly crediting money to his personal account with the Syracuse Trust Co. for mission use.26 One example of this was provided, and it seems some 800 yen was given for use at the hospital in Pyongyang.27 Loeber then traveled to the U.S. sometime in 1911, which he said was for the purpose of personally providing his accounting records to the parent board and, presumably, sorting out the matter.

Discovering individual intent in official records is challenging. However, there are several possibilities that bear consideration. An examination of the documents provided to the court suggest that between the WFMS’ audit, the parent board’s audit [in the U.S.], and Loeber’s refusal to show records of mission matters that went through his personal account, Loeber may have been attempting to pit those on the mission field against the Methodist board in the United States in order to advance an entrepreneurial agenda. This could have been the case if Loeber was indeed trying to cover up any business he might have been doing on the side as a missionary. Another interpretation of the documents could imply individuals like Bunker may have had something else against Loeber, for one of the reasons Loeber claimed to have directly brought the parent board into the matter is that he thought “the people on the field in Korea were prejudiced”.28 In Loeber’s own words, he felt “obliged to account to the ladies in America [the parent board]” rather than the treasurer and auditing committee in Korea. He also thought, according to his record, that going to them directly would avoid litigation.29 Another important point to consider is that Loeber stated he was “accounting for Yen 19595.76 more than appears on the books of the W.F.M.S. of Korea”, offering another explanation as to why Bunker and the auditing committee in Korea were so motivated to have the matter settled – it was an enormous amount of money that they were unable to account for. At the same time, this huge financial discrepancy was, according to Loeber, why he wanted to go directly to the parent board in the U.S. rather than having the missionaries within Korea handle it.30

The accounting issue seems to have been mostly settled by the end of 1911 when the consular court ordered Loeber to pay 650 yen as settlement.31 Another document, signed by treasurer Frey, indicates this payment was accepted.32 However, some debate seemingly continued until 1912, during which time there was some back and forth regarding whether or not the Methodist mission should pay for Loeber’s travel back to the U.S. in 1911. This long arbitration, however, was not the only thing on Loeber’s mind, for shortly after his departure from the mission he appears to have already gone into business for himself.

The Birth of the American Oriental Engineering and Construction Company

Loeber appears to have officially started dealing building materials and hardware in as little as two months after leaving his position with the Methodist mission. In a letter dated June 17, 1910, Loeber’s letterhead shows he had a Western Union cable address setup as “Chaloeber” in Seoul and was dealing light, heat, electricity, sewer, water, and building materials [Figure 1].33 It appears Loeber had used his experience with the Methodist mission to build a business, whether or not he had been delving into private business on the side as a missionary as Bunker claimed. One piece of evidence pointing to this is a note in some accounting records that were provided to the court during arbitration [Figures 2 and 3]. Sargent & Co., the name of an American hardware company which appears in the tops of these records, was one of the companies Loeber would advertise for in the early years of his business. In fact, the earliest known advertisements for Loeber’s business list some of the same types of hardware products from Sargent that were named in the records he provided to the court.

Loeber probably began running advertisements for his business in the locally published Korea Mission Field in 1911, the earliest known ad dating to December of that year. These seem to have continued regularly throughout 1912-1913, and appeared in later years but their frequency is unclear. Such ads are some of the first known mentions of the American Oriental Engineering and Construction Company. A trade report indicates it was in 1913 that the company was officially established in Korea with $100,000 in capital, noting that the head office was in the United States.34 However, the only known record of an AOEC office around this time appears in a 1912 California state record indicating AOEC’s business charter had been forfeited, implying he had at least filed the paperwork for a corporation in that state even if it went defunct.35 This may have, in a practical sense, then made Seoul Loeber’s defacto head office. Yet Loeber likely maintained a base and connections in America of some kind, for even during his civil case in 1911, one of his letterheads listed both Seoul and New York as addresses under his name. Loeber’s networking may be reflected in the Personals section of an American trade magazine published in 1914, where a miner named C. A. Filteau mentioned that while traversing Korea, his address was in the care of AOEC’s office in Seoul.36 Perhaps this mention is also suggestive of Loeber’s connection to the mining community in Korea.

It wasn’t until 1915 that the company appears to have again had a legal business presence in the United States. The National Corporation Reporter published a report that year showing hundreds of new corporations established across the states. The American Oriental Engineering and Construction Company appeared among them with a Boston address in Loeber’s home state of Massachusetts.37 A trade directory also indicated that the business was established in 1915.38 The figure of $100,000 in capital appeared again in The National Corporation Reporter despite being two years after its establishment in Korea. Interestingly, three other employee names were associated with this report. There was a Jason W. Loeber, a William E. McKee, and an M. A. Murphy. We can probably safely assume that Jason W. Loeber was a family member of Charles. No other known records offer any information as to whether these individuals were investors, employees, or something else, but there were mentions of others working for AOEC. A Personal section of the trade journal Mining and Scientific Press, indicated two employees named Theodore P. Haughey and Edgar N. Friend had sailed from Seattle in October 1915 bound for Yokohama, presumably for AOEC related work.39 Haughey’s name would appear again later in other documents, as well as another individual named R. C. Costad. However, little else is known of AOEC staff throughout the years.

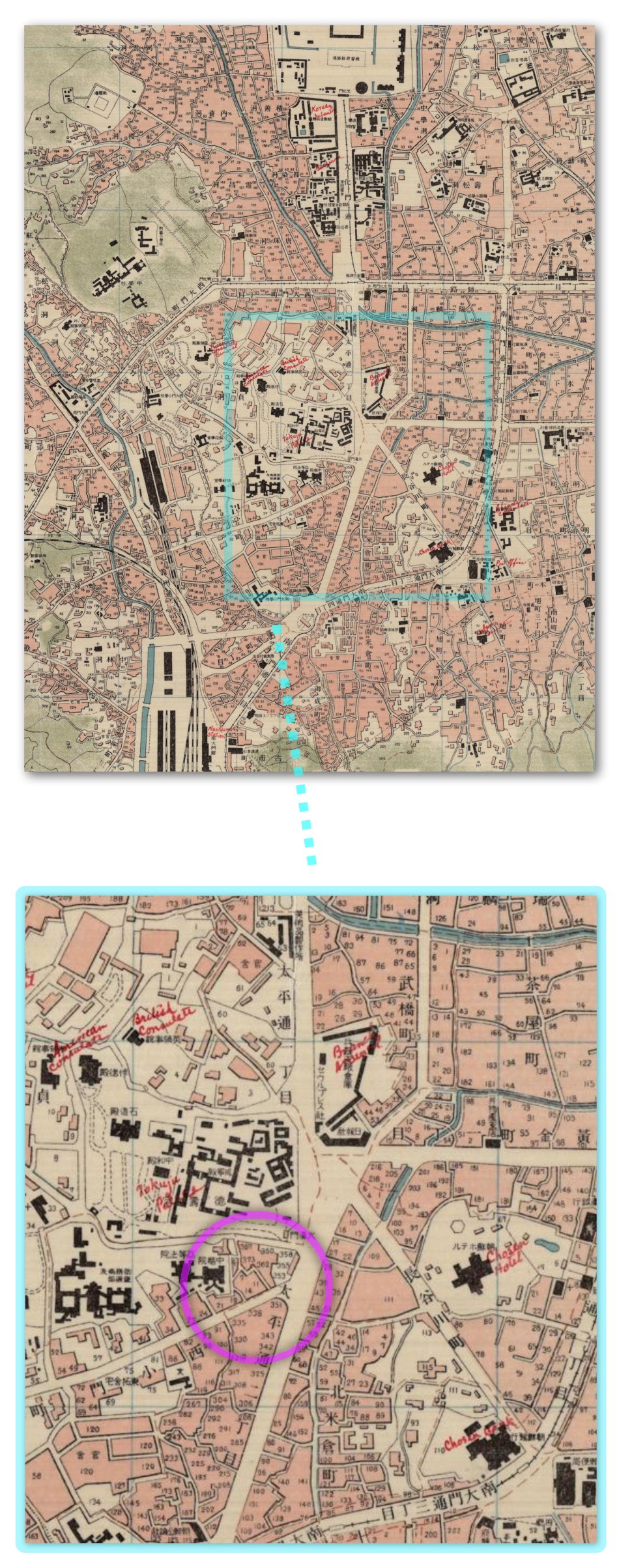

AOEC’s offices in America appear to have changed frequently. When The National Corporation Reporter noted AOEC’s establishment in Massachusetts in 1915, the given address was 39 Strathmore Road.40 In that same year, however, the Boston City Directory indicated it had moved to Room 434, 68 Devonshire.41 In 1917, its Boston address was again different, reportedly at 53 State Street.42 There was then a city directory for San Francisco, California, showing AOEC holding an address at 681 Market Street, suggesting the company had reestablished their California charter that had been forfeited years before.43 Having offices on the both the American east and west coasts would have made good logistical sense, particularly since Loeber advertised being able to quickly ship out goods that they kept on hand in their warehouse. However, little information remains on how well the business was able to perform while being stretched across 13,000 kilometers from Boston to Seoul, with one specific case discussed later on in this article suggesting the company did not function very well. Their office in Seoul, around 1916, was listed as being in the middle of the city at 356 2-chome, Taihei-machi — just two hundred meters south of the Gyeongseong Ilbo newspaper building. Despite AOEC’s advertisements sometimes listing New York, San Francisco, China, Manchuria, and Korea under their business name, no record of offices in New York, China, or Manchuria have been found. The implication is perhaps that these were areas AOEC could do business rather than physical branch locations.

Little is known of Loeber’s life, but it seems a major change took place in 1916. The Korea Mission Field wrote that Mrs. Loeber had departed Korea on July 27th bound for China, with no mention of her husband, Charles Loeber. The note read: “We are sorry to inform the missionary body of Korea that Mrs. Loeber who, during the past year or two, has furnished board for missionaries and their friends who were temporarily stopping in Seoul, can do so no longer inasmuch as she has removed from Seoul to Union Christian College, Peking, China. Mrs. Loeber left Seoul the morning of July 27th. We, of Seoul, deeply regret the departure from our midst of Mrs. Loeber who as a Christian lady respected and loved by all who know her.” 44

It is unclear why Charles was not spoken of in this report, for the Loebers seem to have remained together for years and were both involved in boarding visitors to Seoul in some form of hostelry they began operating in 1914. This is reflected in a report from January that year showing that the Loebers had taken charge of what was formerly Dr. Scranton’s sanitarium building, seemingly renting the entire premises for their use. The sanitarium appears to have simply been a rest house for missionaries in need of a hiatus from their mission work. Whether or not this building was used as Loeber’s business’ office after renting it is unclear, particularly in light of the fact that AOEC was later listed as being on Taihei, however it is possible this was another of Loeber’s business schemes. The sanitarium operated from 1909 until the time Loeber rented it in 1914, described early-on as being eight rooms in a compound upon an elevated site inside the city near Namdaemun. A newer building with electricity, heating, and “baths of various character” was completed on the site between January-July 1910.45 The 1914 report suggests it was this newer building that the Loebers were using, reading: “Mr. Charles Loeber has rented the building in South Gate Street, Seoul, formerly Dr. Scranton’s Sanitarium, and visitors to the city will be interested to know that Mrs. Loeber will be pleased to entertain a limited number of guests, as there are several excellent rooms in the building.”46

In light of this it is important to note that, despite the legal issues from several years earlier, both Charles and his wife appear to have maintained relations with at least some of those in the mission field throughout their years in Korea. During his short time as a missionary, his work on the plumbing for the Methodist hospital at Pyongyang was praised, and he was thanked for his “wise counsel” in “building matters” in The Korea Mission Field.47 The account of the sanitarium also offers another piece of evidence suggesting Loeber and Scranton may have worked together on occasion, the sanitarium perhaps being the structure Bunker claimed Loeber had helped Scranton build.

Then, presumably, Charles Loeber accompanied his wife to China, for further evidence indicates he no longer resided in Korea after 1916.

The End of the American Oriental Engineering and Construction Company

AOEC appears to have gone out of business around the time the Loebers left Korea. Their corporate charter in Massachusetts was forfeited in 1916, and by 1919 the company had been dissolved in that state.48 The company was still listed in Korea in the 1917 The Chronicle and Directory for Asia, yet such directories were typically not truly up-to-date by the time they went to publication, meaning this entry may have been more true for 1916. In the directory, while the company and three employees were listed, Loeber and Haughey were noted as being “absent”, and Costad was “in charge”. Despite being absent, Loeber was still referred to as the general manager and Haughey the sales manager.49

Other evidence from 1916-1917 – papers related to a claim Hubbard & Co. made against AOEC – corroborates the information published in this directory, offering insight into the company’s end. According to these documents, Hubbard & Co., a tool manufacturer and industrial supplier for the U.S., had sent some “300 dozen” shovels to AOEC in Seoul on consignment in 1915.50 Hubbard & Co. reached out to the U.S. state department the following year asking if the consul general in Seoul would be able to ascertain what became of this consignment, the implication being that communication or trust had at least somewhat eroded between Hubbard & Co. and AOEC.

After one to two years of back and forth between the American consul general in Seoul, the state department in Washington, and Hubbard & Co., it was determined that holding AOEC or its employees accountable for the $700-1300 worth of missing shovels would be next to impossible as they had “evidently disbanded, due to lack of funds and discord in their organization.”51 The manager of Hubbard & Co.’s shovel department, Joseph V. Smith, wrote that he had been in contact with Haughey, and that Haughey had indicated the shovels were in Seoul and that he was willing to transfer the products to the consul general for handling and sales. The date for this interaction does not appear in these letters, but it probably occurred in 1915-1916. The last letter in this set of papers dating to July 10, 1917 is enlightening, offering fragments of information on what became of the company and its employees. The letter, written by vice consul in charge Raymond S. Curtice, implied that what remained of the company had been handed off to or commandeered by a local Chinese individual, that the shovels had been sold, and that it was “barely possible” to recover anything from their dealings with AOEC. His words also indicate that the closing of the company was unclear and that Costad had “assumed charge of the Company’s property” in 1916 before later vacating to China. The vice consul wrote:

“…so far as I have been able to learn from the Chinese employee who now seems to be temporarily in charge of the office of the Company in question, the shovels from Messrs. Hubbard and Company have all been sold. It may be remarked that about a year ago a former employee of the Company, Costad by name, assumed charge of the Company’s property and opened an office under the name of the American Oriental Engineering and Construction Company, though by what right or with what powers from the Company I have been unable to learn. This man is now absent from the country, in China I am given to understand, and the date of his return is uncertain. The rumor is that he will not return at all.

“Under the circumstances I doubt if anything can be done at this end by Messrs. Hubbard and Company to recover their shipment, as I feel confident that Mr. Costad was in no way the legal representative of the American Oriental Engineering and Construction Company and that Company was at fault in not providing for the proper safeguarding of their property. It is barely possible that something might be recovered by court proceedings against Mr. Costad, but the distance of the plaintiffs from Chosen and the difficulty of lawyers would seem to make such recourse inadvisable. Furthermore, even in case a favorable judgment were secured, it is doubtful if the defendant would be able to pay.”52

Despite the claims made in this 1917 letter, AOEC did make its way into the 1920 publication of The Chronicle & Directory for Asia, leaving more questions than answers.53 The company, however, did not appear in later editions of the directory, further suggesting the company had gone out of business.

Charles’ name has also been challenging to find in any historical materials after this time. His wife appears to have made it to China where there was a Mrs. I. K. Loeber mentioned in a 1918 report, being secretary to the dean of the Union Medical College at Peking [Beijing].54 What happened to Charles, however, remains a mystery. One possibility is that he, perhaps along with Costad or Haughey, went into business in China. However, a search for their names in directories from that period has proved fruitless. Another is that Charles Loeber rejoined the Methodist mission in some capacity. However, his name also appears absent from Methodist publications around this time. There is then the more unfortunate possibility that Charles Loeber could have died. Or perhaps he moved back to the United States. However, again, a search for his name in directories, or newspaper obituaries, has not yet revealed anything.

The Potential Impact of the American Oriental Engineering and Construction Company on Korea

The name of the American Oriental Engineering and Construction Company carries weight and appears impressive on paper, perhaps even suggestive of Loeber being a structural builder or contractor of some kind. And while it remains possible he remained a builder of sorts given he served as a building “superintendent” for some Methodist projects, the remaining evidence all points to AOEC simply being a product dealer representing various American companies in Korea. If true, the reason for the company’s somewhat misleading name then remains unclear. Perhaps it was merely for marketing reasons. Then again it may be suggestive of the direction Loeber wanted the company to take, eventually becoming a builder or contractor. However, as a “consulting engineer,” as the Boston Chamber of Commerce’s records called him, Loeber may have simply advised buyers on what their building projects needed and then handled the ordering and shipment of their products.55 Regardless, an exploration of the company’s advertisements helps in understanding the potential impact AOEC had on the Korean peninsula, however small, by bringing in these various products from abroad.

The products that seemed the most unique to Loeber’s business were (1) a specific “paint” made by the Alabastine Co., (2) an early type of drywall made by the Plastergon Wall Board Co., and (3) raw pine from the state of Oregon.

Alabastine came in a powdered form and, after being mixed with water, could be applied to any type of surface regardless of material or texture. One five-pound package was thought to be able to cover 450 square feet of wall.56 It was touted as being perfect for hospitals and schools due to its “sanitary” nature, and was used in various public institutions, including churches.57 The company typically shied away from clearly stating the material makeup of their product, but a 1915 explanatory “how to” publication indicates its base was gypsum.58 Being both rock-based and air permeable, Alabastine would have been able to remain both moisture and mold resistant, giving it a reputation for being hygienic.59 The product had the potential of working well in Korea’s humid summers.

Plastergon was reportedly a chemically-treated fiberboard meant to serve as a replacement for lathe and plaster.60 The Architect and Engineer called the Plastergon Wall Board Co. a “pioneer manufacturer” of wall board products, the name itself seemingly a pun implying plaster and lathe were no longer needed in wall construction.61 Without more information, it remains unclear as to how Plastergon would have fared in Korea.

It’s also unclear where Loeber sourced the Oregon lumber AOEC advertised.

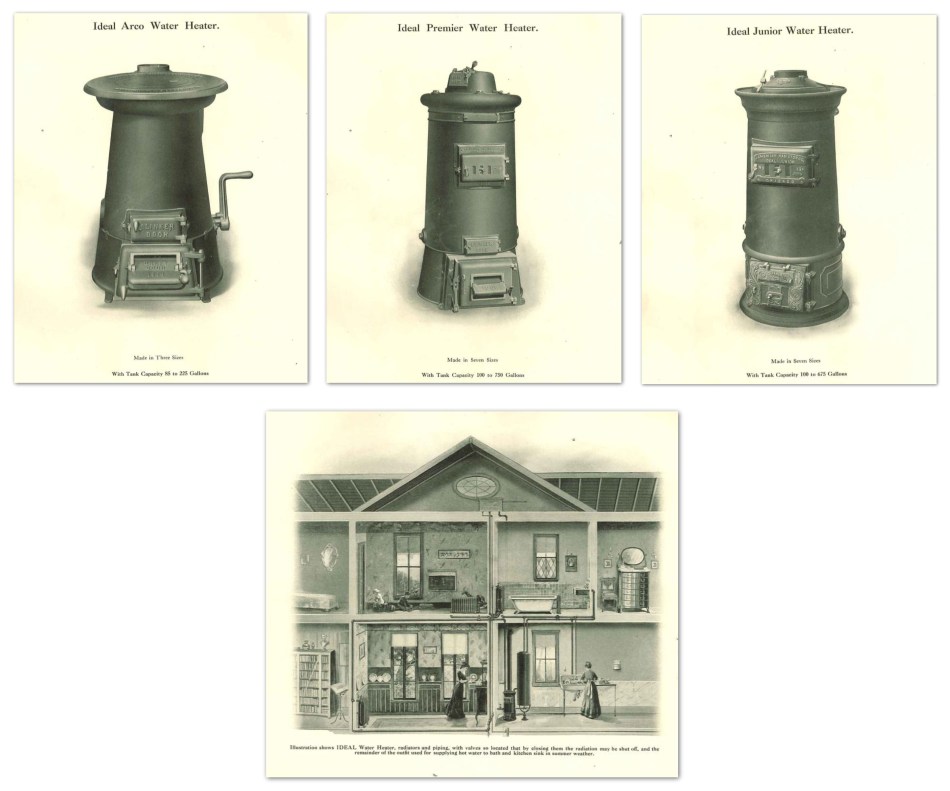

The larger companies represented by AOEC were Sargent & Co., Hubbard & Co., and the American Radiator Co. He also advertised for the Wheeler-Osgood Company [Figure 6], another hardware supplier offering doors, millwork, etc., but appears to have stopped doing so early on. The hardware and products provided by Sargent and Hubbard were not very unique as American missionaries had been obtaining similar products for years from Montgomery Ward & Co. The products AOEC advertised from the American Radiator Co. appear to have been everything one would need for a modern, centralized piped system, but standalone boilers that were popular within the missionary community at the time were also, of course, available. To be sure, all that the AOEC advertised in The Korea Mission Field were products that missionary homes, hospitals, schools, and churches would have wanted, and Loeber seems to have understood this well. Several letters and mission reports from the 1900s lamented the difficulty of procuring structural lumber as Korea was not as heavily forested as it is today. The American northwestern pine advertised by AOEC could have met this demand. Westerners also wrote of various vermin in the home, and as the various Christian missions continued to build more hospitals across the Korean peninsula, Alabastine and Plastergon could have met their need – however perceived or real – for cleaner indoor spaces. Given his work with the Methodist mission when he arrived in Korea, this demand for building hardware and equipment is likely the reason Loeber went into business.

Conclusion

In review, AOEC’s impact on the material makeup of Korea’s buildings in the 1910s was probably quite small. After all, Loeber’s business seems to have only lasted for about six years before going under. Yet it is interesting to consider that some buildings, somewhere, may have implemented these imported products. Perhaps it was Loeber’s work on the Methodist hospitals that led to him partnering with the Alabastine Co., and perhaps there were a few buildings in Korea that made use of his imported northwestern American pine. At a time when walls were typically plaster and clay or masonry, maybe Plastergon was the first type of drywall to make it to the Korean peninsula. Unfortunately, without more evidence, only the potentialities for material change can be considered here.

It bears mentioning that while the reasons for AOEC’s failure to stay in business remain unclear, the types of services and products Loeber provided in the 1910s continued to be marketed by others after this time and into the 1920s. J. H. Morris & Co. reportedly dealt electrical supplies, mining equipment, and American hardware, while W. W. Taylor & Co. and Y. S. Lew advertised their offerings of various paint-like products. Perhaps companies like these took over the market space that AOEC once occupied.

All of this took place within an increasingly urbanized Korea that demanded newer types of buildings and building products, allowing for entrepreneurs like Loeber to try their hand at competing in this market. His niche appears to have been the missionary community, yet there were other sectors with other demands to consider and construction in Seoul was booming. To be sure, it remains unclear as to whether AOEC at all dealt with local Korean, Chinese, or Japanese in other building projects. Perhaps, had Loeber done so, his company would have fared better.

Footnotes and Citations

1 In a 1910 statement given when taken to court (held by American consul-general, Scidmore), Loeber stated he was 32 years old, placing his birth year at 1878. His death remains unknown. Memorandum and statement at court, August 11, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 28 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

2 Alumni Record and General Catalogue of Syracuse University, v. 3 p. 1 (New York: Alumni Association of Syracuse University, 1911): 105. HathiTrust Digital Library.

3 Alumni Record and General Catalogue of Syracuse University, v. 3 p. 1 (New York: Alumni Association of Syracuse University, 1911): 95. HathiTrust Digital Library.

4 “Journal of Daily Proceedings,” Minutes of the Troy Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church (April 1908): 68. HathiTrust Digital Library.; “Journal of Daily Proceedings,” Minutes of the Troy Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church (April 1908): 75. HathiTrust Digital Library.

5 “Church News”, The Christian Advocate, v.83 n.21 (May 21, 1908): 864. HathiTrust Digital Library.

6 Memorandum and statements at court by Loeber and Bunker, August 11, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 28-33 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

7 Loeber wrote that he arrived in Korea “on or about June 27th”. Memorandum and statements at court by Loeber and Bunker, August 11, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 28-33 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

8 Minutes of the Annual Conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church (New York: Eaton & Mains; Cincinnati: Jennings & Graham, 1909), 151. HathiTrust Digital Library.

9 “Church News”, The Christian Advocate, v.83 n.21 (May 21, 1908): 864. HathiTrust Digital Library.

10 Minutes of the Annual Conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church (New York: Eaton & Mains; Cincinnati: Jennings & Graham, 1909), 151. HathiTrust Digital Library.

11 Rosettas Hall and Esther K. Pak, “Woman’s Medical Work, Pyong Yang,” The Korea Mission Field, v. 5, n. 7 (July 1907): 110-111. Moffett Korea Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary Library.; Letter from W. A. Noble [William Arthur Noble] to American Consul General George H. Scidmore, September 30, 1911. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized pages 13-15 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

12 Statement at court by D. A. Bunker [Dalzell Adelbert Bunker], August 1, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized pages 25-26 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

13 In court, Loeber is documented as saying “I presented my resignation to said Board and it was accepted January, last, I think, to take effect April 30th, 1910.” Memorandum and statements at court by Loeber and Bunker, August 11, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 28-33 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

14 “Church News”, The Christian Advocate, v.85 n.22 (June 2, 1910): 786. HathiTrust Digital Library.

15 There are several inaccessible remaining consular documents in the National Archives and Record Administration dating to 1909 labeled as accounts for various Methodist mission matters related to Loeber. Without reading the documents, it is unclear whether these were just records held by the American consul or were also related to Loeber’s accounting issues and civil suit. To be clear, these documents can be accessed in person at NARA, but are remotely unavailable to me at present. These are located in RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915), National Archives and Records Administration. They are also labeled as “Bunker House Account with Mission Building Fund”, “Cable House Account with Mission Building Fund”, and “General Account of the Mission Building Fund” in The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

16 Bunker had been in Korea since 1886 and then taught at Gojong’s government school. He served the Methodist mission for decades, briefly leaving in 1897 to join the American Mining Company before returning to mission work. Several of the court documents clearly state Bunker as the plaintiff and Loeber the defendant.

17 Letter from American vice consul general Ozro C. Gould to Charles Loeber, August 5, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 24 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

18 Letter from D. A. Bunker to Mr. [Charles] Loeber, June 16, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 37 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

19 See footnote 42 in Dae Young Ryu’s section entitled “Creating an Appetite and Selling American Merchandise”. Dae Young Ryu, “Understanding Early American Missionaries in Korea (1884-1910): Capitalist Middle-Class Values and the Weber Thesis,” Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions, v.113 (January-March 2001): 93-117. OpenEdition Journals.

20 Memorandum and statements at court by Loeber and Bunker, August 11, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 28-33 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

21 Report of Auditing Committee [Women’s Foreign Missionary Society], June 23, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 35 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

22 Memorandum of audit for year closing December 31, 1909 on Garrett Biblical Institute paper. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 47 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

23 Report of Auditing Committee [Women’s Foreign Missionary Society], June 23, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 35 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

24 Report of Auditing Committee [Women’s Foreign Missionary Society], June 23, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 35 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

25 Memorandum and statements at court by Loeber and Bunker, August 11, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 28-33 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

26 Letter from Charles Loeber to American consul general George H. Scidmore, September 30, 1911. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 10-11 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

27 The document states “Pyeng Hospital”, likely shorthand or an error referring to Pyengyeng [Pyongyang]. Letter from Charles Loeber to American consul general George H. Scidmore, September 30, 1911. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 10-11 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].; The aforementioned note in the Korea Mission Field specifically indicated he was working on the plumbing. Rosettas Hall and Esther K. Pak, “Woman’s Medical Work, Pyong Yang,” The Korea Mission Field, v. 5, n. 7 (July 1907): 110-111. Moffett Korea Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary Library.

28 Letter from Charles Loeber to American consul general George H. Scidmore, September 30, 1911. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 10-11 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

29 Letter from Charles Loeber to American consul general George H. Scidmore, September 30, 1911. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 10-11 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

30 Letter from Charles Loeber to American consul general George H. Scidmore, September 30, 1911. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 10-11 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

31 Court decision signed by Gio. N. Seid [illegible] Consul General of the United States of America, October 3, 1911. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 19-20 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].; Note that the consul general’s name here is illegible and “Gio. N. Seid” is a partial estimation.

32 Letter from Lulu E. Frey to American Consulate General of Seoul, October 3, 1911. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 21 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

33 Letter from Charles Loeber to Mr. [D. A. Bunker], June 17, 1910. RG 84, 84.3 Records of Consular Posts, 1790-1963, Seoul, Korea, 1884-1936, Entry 816, Box 9, (Miscellaneous Papers, Civil and Criminal Court Cases, 1910-1915) Arbitration between Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and Charles Loeber, September 29, 1911 to October 3, 1911. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 38 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

34 “Establishment of Companies in Chosen,” Daily Consular and Trade Reports v. 3 n. 221 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1915): 1549. Google Books.

35 Certified Copy of Compiled Statement of Domestic Corporations Whose Charters Have Been Forfeited and Foreign Corporations Whose Right To Do Business In This State Has Been Forfeited (California State Printing Office, 1912): 5. HathiTrust Digital Library.

36 “Personals,” The Colorado School of Mines Magazine, v. 4 n. 9 (September 1914): 215.

37 “New Corporations,” The National Corporation Reporter, v. 50, n. 21 (July 1, 1915): 854. HathiTrust Digital Library.

38 B. Olney Hough, Export Trade Directory (New York: American Exporter and Johnston Export Publishing Co., 1917), 208. HathiTrust Digital Library.

39 “Theo. P. Haughey, accompanied by Edgar N. Friend, both of the American-Oriental Engineering & Construction Co., sailed from Seattle early in October for Yokohama.” “Personal,” Mining and Scientific Press, v. 111 (October 16, 1915): 610. HathiTrust Digital Library.

40 “New Corporations,” The National Corporation Reporter, v. 50, n. 21 (July 1, 1915): 854. HathiTrust Digital Library.

41 One American source calls Loeber a “consulting engineer.” The Boston Directory Containing the City Record (Boston: Sampson & Murdock Company, 1916): 2234-2235. Allen County Public Library.

42 B. Olney Hough, Export Trade Directory (New York: American Exporter and Johnston Export Publishing Co., 1917), 208. HathiTrust Digital Library.

43 Crocker-Langley San Francisco Directory (San Francisco: H. S. Crocker Co., 1916): 2172.

44 “Notes and Personals”, The Korea Mission Field, v. 12, n. 8 (August 1916): 227. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary Library.

45 Published letter from W. B. Scranton to the editor of the Korea Mission Field. The Korea Mission Field, v. 5 n. 9 (September 1909): 158-159. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary Library.

46 “Notes and Personals,” The Korea Mission Field, v. 10, n. 1 (January 1914): 29. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary Library.

47 Mrs. Rosettas Hall, M.D. and Mrs. Esther K. Pak, M.D., “Woman’s Medical Work, Pyong Yang,” The Korea Mission Field, v. 5 n. 7 (July 1909): 110-111. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary Library.

48 See the “Forfeited Charters of Foreign Corporations”section of the following text. Certified Copy of Compiled Statement of Domestic Corporations Whose Charters Have Been Forfeited and Foreign Corporations Whose Right To Do Intrastate Business In This State Has Been Forfeited (California State Printing Office, 1916): 45. HathiTrust Digital Library.; See the “Special Acts” section for 1919 regarding Chapter 111. Special Acts and Resolves Passed By The General Court of Massachusetts In The Year 1919 (Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1919): 67. HathiTrust Digital Library.

49 The Directory & Chronicle for China, Japan, Corea, Indo-China, Straits Settlements, Malay States, Siam, Netherlands India, Borneo, The Phillippines, and &c., (London: The Hongkong Daily Press Ltd., 1917): 657. HathiTrust Digital Library.

50 Letter from Jos. V. Smith to the Department of State, May 9, 1917. Record Group 84: Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, 1788 – 1964. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 8 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

51 One letter from Hubbard & Co. indicates the cost was approximately $700. A later letter indicates the cost was $1300. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear. Letter from [illegible] to American consul general Ransford S. Miller, February 12, 1917. Record Group 84: Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, 1788 – 1964. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 3 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].; Letter from Jos. V. Smith to the attention of Mr. [Ransford S.] Miller, February 10, 1917. Record Group 84: Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, 1788 – 1964. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 2 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

52 Letter to the Secretary of State at Washington from American vice consul Raymond S. Curtice, July 10, 1917. Record Group 84: Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, 1788 – 1964. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed on digitized page 10-11 via The Archives of Korean History [Jeonjasaryugwan].

53 The Directory & Chronicle for China, Japan, Corea, Indo-China, Straits Settlements, Malay States, Siam, Netherlands India, Borneo, The Phillippines, and &c., (London: The Hongkong Daily Press Ltd., 1920): 569. University of California.

54 Thus far, there has been no way to conclusively ascertain whether or not the I. K. Loeber referred to in this report was Charles Loeber’s wife. However, given the rarity of the name at the time and the report that she moved to Beijing to join Union Christian College, it remains probable that I. K. Loeber was Charles’ wife. China Medical Board: Fourth Annual Report (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, 1919): 27.

55 One American source calls Loeber a “consulting engineer.” The Boston Directory Containing the City Record (Boston: Sampson & Murdock Company, 1916): 2234-2235. Allen County Public Library.

56 Undated Alabastine Co. informational pamphlet. Alabastine: The Sanitary Wall Coating (Alabstine Co.), 10-11. Building Technology Heritage Library.

57 Alabastine Home Color Book (1928), 18. Building Technology Heritage Library.

58 Church’s Alabastine and how to use it to the best advantage (Alabastine Co., 1915): 7. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library and Canadian Pamphlets and Broadsides Collection.

59 This comment is based on the general work of the Building Science Corporation and Joseph Lstiburek, whose research covers the most up-to-date understanding of building enclosures, building failures, energy efficiency, etc, today. Interestingly, the Alabastine Company also appears to have understood this, at least to some degree.

60 The Architect and Engineer, v. 34 n. 3 (San Francisco: October 1913): 143. San Francisco Public Library.

61 The Architect and Engineer, v. 36 n. 1 (San Francisco: February 1914): 128-129. San Francisco Public Library.

The ideas, articles, and images featured here are, unless otherwise noted, the intellectual property and copyright of Nate Kornegay, 2021. All rights reserved. Some images have been used according to standard rules of Fair Use, while others are open-access materials or have been licensed or otherwise permitted to be published on this website. Images from the Nate Kornegay Collection and photographs made by the author may not be reproduced without permission.

0 comments on “The American Oriental Engineering and Construction Company (1910s)”