The Westernization of Korean buildings in the late nineteenth century was not a planned stylistic shift, nor was it an architectural movement in and of itself. Rather, initially it was the modification and alteration of what was already available to foreigners on the peninsula at the time. Like the first compradoric buildings of Shanghai and the giyōfū architecture of Yokohama, Westernized hanok were derived from the wants and needs of newly-arrived Westerners in a land where little foreign architecture had ever been built.

It was in the mid-1880s that Korean architecture was first modified with Western features. As foreign diplomats bought up land for both personal and state use, they set about altering the structures to suit their lifestyles. Some governments used these buildings temporarily until better arrangements could be made while others maintained and improved their Korean structures over time. However, during a time in which construction materials were difficult to source quickly and the commercial importance of Korea was still being assessed, buildings like the German, American, and British consular offices in Seoul remained in “made over” Joseon buildings in the 1880s.1 While later brick buildings were more widely appreciated by visitors and the foreign community in general, there were those who praised, and even preferred, Korean vernacular architecture, which “lends itself very well to remodeling.”2 Amidst a growing Western community, one anonymous correspondent in Seoul wrote to the North China Herald in 1888 that the “building of houses semi-foreign or entirely so, is quite the rage of the day over here, and several very comfortable and fine looking buildings have been finished.”3

Diplomatic missions were generally old yangban estates, with most cases probably built on oryang frames — frames of five timber beams. As the foreign community grew, more hanok were modified. To be sure, by 1892 it was known that the “houses which foreigners occupy are, with one or two exceptions, native houses altered by building additions, knocking out partitions and adapting them in various ways to our different habits. As had already been mentioned, the rooms of a house are very small; but since the partitions are often nothing but a framework of wood covered with paper, they are easily removed, and several rooms thus thrown into one make comfortable living quarters. Foreigners usually purchase houses from the better class, and as these houses generally have plenty of ground around them, they are easily transformed, with but little outlay, into pleasant abodes with the accessories of lawn, flower-garden and often tennis-courts. Repapered and furnished, their paper-covered windows replaced with others of glass, these native houses make very comfortable residences both in summer and winter. The abundance of windows and doors makes ventilation in summer easy, while these same vents can in winter be so sealed up with the tough paper which can be obtained there in abundance as to be comfortable and cheery in the steady cold of winter. The shape of the houses, built, as we have shown, around a hollow court, allows plenty of light into all the rooms, even though the eaves do overhang four or more feet.”4

These Korean structures were frequently altered to suit the needs of newly formed protestant churches, where growing congregations led to building renovations. In Pyongyang, missionaries decided to expand their church building at the east gate by putting “the porch into the room” and “to floor what is now the kitchen thus joining the two wings of the building so as to place the pulpit at their junction, allowing the preacher to face the men gathered in one part and the women gathered in the other.”5 While some nineteenth-century Westernized Korean buildings were renovation projects, others were newly built from the ground up. When the English Church Mission completed its 1,250 square foot “Church of the Advent” at the end of 1892, its frame was apparently built in the Joseon style. Even its altar railing — a Western-Christian architectural feature — drew from classical Sino-Korean geometry.

As Western-style brick and glass became more readily available over the next decade, what we now call hanok began to take on American characteristics.6 Bay windows were added, lattice porch skirting covered the cavities under toenmaru, and brick was mortared over facades. Hanok like those used by the American Mission appear to have had their toenmaru widened to imitate Western porches. Drainage gutters and roof extensions were added at the eaves as well. By the turn of the century, these “semi-foreign Korean houses” were “nearly all one story brick veneered mud houses, with tile roof, but the rooms were large and comfortable with glass windows and many American conveniences.”7 For example, such brick veneer was applied in 1901 to W. H. Emberley’s station hotel near the railway terminus.8 The residence of a Seoul Electric Company employee, described as being “a little corner suggestive of California,” similarly had a brick veneer.9 Interiors, too, were a mixture of Western and Korean furnishings, sometimes “Orientalist” in taste and style.

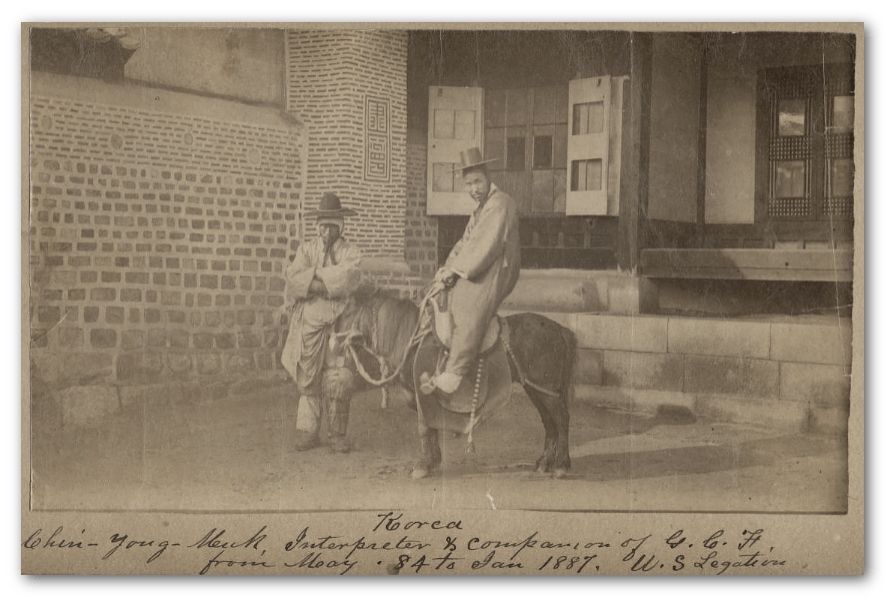

The early Westernization of Joseon architecture is then well represented by the American legation. Modified over time from a neglected hanok estate formerly owned by the Min family, the grounds reportedly contained “seven principal houses, besides servants’ quarters and outhouses” – all originally Korean in design.10 The first U.S. Minister to Korea, Lucius Foote, and his wife set about improving the area after purchasing it subsequent to their arrival in 1883. Yet such endeavors took time in those days. The help of a ship’s painter allowed for the legation’s outbuildings to be coated in grey and red trim,11 and after being furnished by “Japanese artists”, the Footes retained “all of the rich oriental architectural details within and without”.12 They especially treasured the “massive dark beams and rafters of the Legation offices and drawing-rooms”,13 features that Horace Newton Allen also stated as being preserved, much “to the intense delight of visitors of an artistic temperament”.14

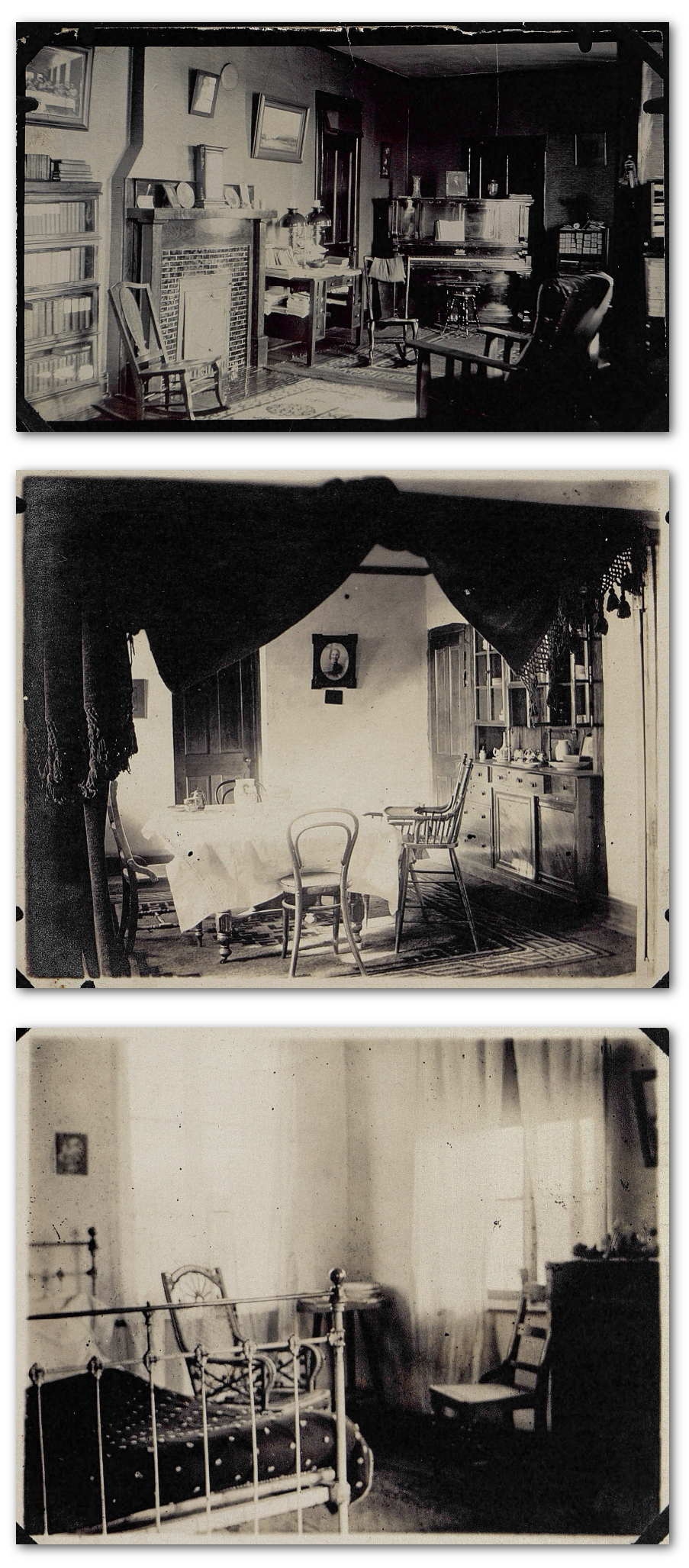

The legation was continually altered over time. Around 1884-1885, American naval attache and chargé d’affaires George Clayton Foulk produced a number of photographs indicating that glass windows had been installed in at least one of the legation buildings.15 By December of 1891, the residence was covered with brick, its roof beams varnished and “the rest of the woodwork … white.”16 It was also described as having a poêle russe, which usually refers to a large Russian-style masonry stove, however the context here is unclear.17 Not only were the legation grounds made in the image of middle-class American gardens, but the buildings were becoming more hybridized by the 1900s. Inside the residence, white patterned Korean wallpaper was abandoned for a dark color scheme, contrasting with light floor carpeting featuring a geometric “ㄹ” border pattern. The floor-based style of living typically found in hanok was also rejected as Western-style cushioned chairs and sofas came to furnish the space. Electrically wired, the home’s Victorian lamps sat atop brass decorated Korean chests. The hybridization of design continued in the windows, whose Sino-Korean style lattice frames symmetrically held glass panes in their centers. In the drawing room, even the lines in the head of the the bay window’s woodwork reflected the same geometric carpentry found in royal Joseon architecture.18 No other feature embodies this architectural fusion more than the home’s fireplace. Constructed in Western form with stone and thin brick, its decorative pattern was clearly influenced by the clay kkotdam designs found in Gyeongbok palace.

Whether coincidental or purposeful, the interior of the legation residence began to take on characteristics of the American Craftsman style by the mid 1900s. To be sure, the columned partitions added between the drawing and dining rooms mirror the Arts and Crafts bungalows later defined by architectural firms like Greene & Greene. This amalgam of styles, designs, and materials simultaneously demonstrated the synthesis and alteration of architecture in early modern Korea. Furthermore, the evolution of the American legation buildings represents a degree of cultural pluralism affecting a newly urbanizing Seoul, where artisans, laborers, and merchants from differing nationalities seem to have had a hand in how buildings like the legation residence appeared.

While the American legation is an arguably attractive example of Western-Korean architectural fusion, even it may have been somewhat unusual compared to the structures modified and built by the missionary community. To be sure, it was the pursuit of an American middle class lifestyle, chiefly by missionaries, that directly led to this hybridized style in many cases, best reflected in the research of Dae Young Ryu.19 While greatly appreciated by those living there, some visitors to Seoul found such architecture off-putting. Not only did Elias Burton Holmes dislike how modernization was disrupting Seoul’s “traditional” aesthetic, but when British politician Ernest Frederic George Hatch passed through in the 1900s, he called the city “a great monotonous waste of houses with a Western veneering, which assorts somewhat ill with the body upon which it is laid.”20

There was a great deal of variance in the additions and modifications made to such buildings, meaning hybrid Western-Korean buildings were not homogenous. An examination of two missionary homes from the period offers further clarity in understanding how Joseon architecture and Western design were fused together, in addition to how its execution varied. When Presbyterian missionary Eugene Bell completed his family’s residence in Mokpo in 1899, it featured a Korean frame and giwa roof but followed Western form, centered on a raised porch with lattice skirting and railing. The Bell home also had a Russian masonry stove, a distinctly non-Korean feature.21 The port city in which the Bells had built their new home was very much undeveloped at the time, being the only Western family amongst a slew of Japanese settlers, local Koreans, and a few Chinese individuals. Perhaps as a result, the home was visibly far from perfect, and yet they were still able to make use of the available laborers and resources to have such a building constructed. In a lengthy letter to his mother, Eugene Bell sketched a floor plan and described his home’s construction:

“The painter, who is a Japanese, lives in Seoul. I am expecting him on every steamer. It will take nearly a month to put in all the glass with putty and do all the painting and varnishing. Until you have worked nearly a year on a house, and then lived for months in a shanty as we have done it is impossible for you to conceive how nice it is to be at least in a nice large room with glass windows like this is. We have three nice large windows in this room run on weights.”

“The room is 16ft square; ceiling 10ft high, and opening off of it is a bathroom, and also a good large dressing room with innumerable shelves, wardrobes, cupboards, etc. The Russian stove, so far, is a joy to our hearts. We find that in this weather which is not very cold that with a fire made of 15 sticks of wood in the morning and another of 10 sticks at night that this one stove keeps warm during the 24 hrs. our bed room 16 ft sq. sitting room 16 ft sq. and bath room 6×8. The location is like this…” (See Figure 18 below).

“A Russian stove is nothing more than a large oven built with brick, the flue from which runs round and round and round rising the width of the flue with each round, till it finally goes out at the top . . . All of the fire is put out at once and when the wood is well burnt a damper up near the ceiling is closed which entirely shuts the flue and all the heat is kept in. Our stove is 4×5 feet. All this immense mass of brick become very hot and gives off the heat so gradually that two fires a day are sufficient for the 24 hrs . . . This one is fired from the bathroom, no wood being brought in the bed or sitting room, and as the ashes have to be taken out once or twice a winter it will not make any dirt in the house. The stove does not look like a stove at all. The bricks are plastered and as it goes straight up to the ceiling it simply looks like an offset in the room.”

“We have lived in several different houses since we have been out here, all of which were fairly comfortable and some we thought were right nice but this is far superior to anything we have ever had and I think will prove to be both convenient and comfortable in every way.”22

In contrast, the residence for the family of James E. Adams at Daegu was of a much higher quality, aesthetically attractive to a degree not found in the rough-around-the-edges Bell home. The city had better access to workmen, who were to be found in (relatively) nearby Busan. The house was built upon a stone foundation, covered in neat brick, and crowned with a Joseon giwa roof. Clearly well-thought out and built by skilled carpenters (or perhaps well-supervised), its Western-style dormer windows are significant features that were very unusual at the time, signaling further fusion of American culture and design into the local textures. The house, however, reportedly did not have attic space, suggesting the dormers were either added for increased light or merely for aesthetics.23 The interior, though plain, was entirely Western. Not only were most of the furnishings imported, but the home’s baseboards and crown moulding further made each space effectively non-Korean. This is despite the fact that Adams “deprecate[d] strongly” missionary residences built in a foreign (Western) style.24 (To be fair, it is unclear whether or not Adams was involved in its construction; these matters were usually handled by the Mission). In some ways, the Adams house leaned closer to being a Western-style house than a Joseon hanok, yet still representative of hybrid Western-Korean buildings constructed at the time.

The involvement of Western personalities in modifying Joseon architectural design is also highlighted by missionary work in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Pyongyang. It was there that an American Midwesterner named Graham Lee left a significant mark on the Korean landscape. A Presbyterian missionary and chairman of the mission’s building committee at the time, Lee has been credited as the designer of some of the most noteworthy examples of modified Joseon architecture in early modern Korea – the most well known being Pyeng Yang Central Church (Pyongyang).25

Lee was little prepared for such construction work, overseeing the initial stages of Pyeng Yang Central Church himself with no known formal training and without letting any contracts.26 The gravity of the situation, however cautiously worded, was expressed in a letter from Lee to his parents in which he called the building “a pretty large problem to tackle”.27 Lee wrote that he had “been working on this problem some months”, attempting to end on a positive note by indicating he was satisfied with the construction preparations – despite realizing “what a job it is for a man of my experience.”28 What little ability and knowledge Lee possessed he broadly credited to his father, from whom he claimed his “mechanical ingenuity” was inherited.29

The missionary continued by offering a candid look at what was happening with the church project between the time construction reportedly began in the spring of 1900 and the time of the laying of the cornerstone on June 25.30 The letter, dated May 27, places Lee back in Pyongyang after having just returned from Seoul where he got “some material for our new church”.31 There, he “bought an anvil and some blacksmith tools”, explaining that “on the church site I’m going to rig up a blacksmith shop to make the bolts and irons for these trusses. Now all this work of making bolts and cutting threads I have to teach some man how to do and that takes a lot of time.”32

The roof trusses for Pyeng Yang Central Church were to be of a “36 foot span” hoisted by a rope system on a “derrick” that Lee would have had to rig himself. The knowledge of how to do this, according to Lee, came from a summer season on his uncle’s farm in which he “spent a lot of time learning how to make all sorts of knots with rope from a sailor who was working there that year”. So important was this single experience in relation to his new church project that he claimed “without that knowledge I would simply be lost.”33

Lee’s description of his work in adding a second floor to the house of Dr. John D. Wells at Pyongyang may offer some insight into how he planned to use his knowledge in building the much larger Central Church building. Of Wells’ Joseon-styled house, Lee wrote: “The posts are about nineteen feet long and a foot in diameter at the large end and each post had to be raised, marked, lowered, framed and then raised again. I have a big double block using ¾ rope, and this I rigged to a long pole set in the center of the building and steadied with guy ropes. Then we raised and lowered those posts with the greatest ease. The carpenters never got tired praising that block.”34 In addition to Graham Lee’s involvement in the Wells’ house, William Martyn Baird, the president of the still-forming academy, implied that it was Lee who ensured he and his wife had a “very comfortable house” in Pyongyang, “which, but for a delay in the coming of the hardware, would have been ready for use upon our arrival.”35

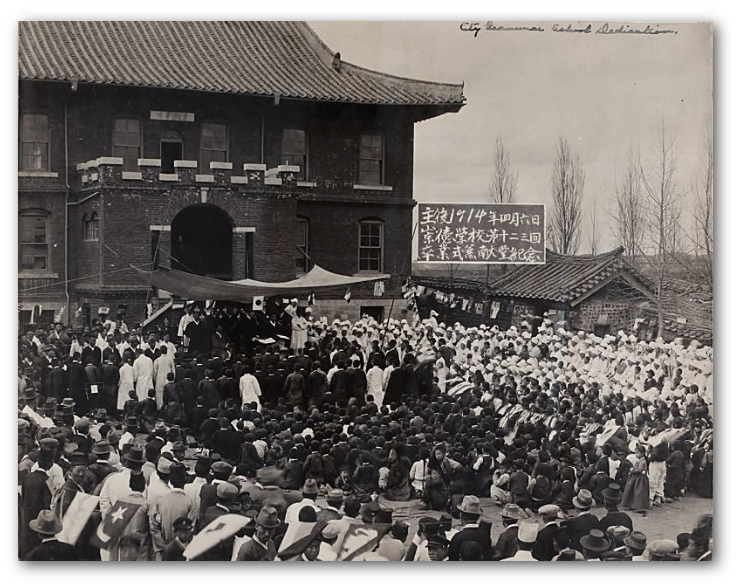

Pyeng Yang Central Church, whose construction was ongoing at the time, was built in two stages — the first expected to have been finished by the end of 1900. Meanwhile, Pyeng Yang Academy (the institution as opposed to a physical structure) opened to a class of about thirty students on September 30 without a dedicated new building as the mission “did not get any school buildings erected” that season.36 The reason for this given by Baird was due to “an unexpected turn in the lumber market as well as to Mr. Lee’s being engaged all summer with the church building”.37 Lee’s preoccupation with Pyeng Yang Central Church would last until the following year of 1901. Construction on the second wing began in April before being quickly roofed by June.38 Galleries [second-floor audience balconies] were hoped to be added by 1902, but it is unclear whether or not these were built.39 The missionary-architect also began construction of the Pyeng Yang Academy building that same spring, becoming “largely occupied in the erection of the building”, of which no detailed construction accounts have been found.40

It is unclear how much credit should be given to Lee as a builder or designer. He was responsible for starting the church project, but he was clearly assisted by others within the Presbyterian community. To be sure, aspects of the technical planning of Pyeng Yang Central Church’s timber frame might be indebted not to Lee, but to Dr. Alfred M. Sharrocks who was a “practical carpenter” arriving in Korea “just in time to render very valuable assistance to Mr. Lee in what has been a truly great undertaking”.41 Without Sharrocks, it is unclear what would have come of the church building for Lee reportedly lacked the knowledge and experience to handle the issue. Certainly, before Sharrocks’ arrival, Lee expressed little confidence in his own ability to handle issues related to framing. The apprehensive Illinoisan went so far as to say that “when you remember that our carpenters know nothing about framing such a structure and that I know very little about the practical laying out of the work, then you can understand how big the problem is.”42

Sharrocks was not the only missionary named in connection with the new Presbyterian construction projects at Pyongyang around 1900. When Graham Lee temporarily left Korea to visit the United States around May-June 1901, another missionary-carpenter by the name of George Leck “took charge of the building operations” at Pyongyang.43 Leck, a Nova Scotian native who had studied at Auburn Theological Seminary and was later ordained at his church in Minneapolis, unfortunately spent little time in Korea, sadly succumbing to smallpox on Christmas Eve, 1901.44 His legacy there as building supervisor, however short lived, might not have been insignificant. He oversaw the rest of the construction of the Pyeng Yang Central Church’s second wing, the Pyeng Yang Academy building, and the additions made to the hospital building there.45

The experimentation with Joseon design, though arguably well-executed in some cases, may not have always been successful. Notes in the William M. Baird Papers suggest that one of the Presbyterian mission’s modified Joseon buildings – the main recitation hall of the Presbyterian Theological Seminary at Pyongyang – had to be torn down around 1916 as its “heavy tile roof” was claimed as being “too much weight for a two story building” and was subsequently replaced by a brick structure.46 The weight of tile roofs on two-story buildings was also a concern for other Western builders, appearing to have been one of the reasons mission stations were always searching for ways to build more “permanent” buildings of brick and stone.

A photograph taken after the Presbyterians’ Pyongyang Grammar School (b. 1910) burned down may offer some clue as to why the issue of tile roofs being too heavy was occurring. The photo depicts a remaining section of the building’s gutted shell, revealing what appears to have been a Western queen post truss system rather than a traditional Korean roof support frame.

The implication becomes that Korean-styled buildings using Western frames could not adequately support Korean giwa roofs — an engineering and technical issue that could have been prevented had formally trained architects been involved. This likely was what was happening when Lee claimed “our carpenters know nothing of framing such a structure” when writing of Pyeng Yang Central Church.47 Rather than being a comment indicating Korean builders did not how to build Korean structures, the issue appears to have been that Westerners were trying to combine Western trusses and frames with Korean roofs. A similar report from then rural Daegu in 1901 also further clarifies this point, explicitly stating that “the Koreans did not know anything about constructing trusses” at the time.48 Supporting Korean roofs with Western trusses was what then probably contributed to the issue of heavy tile roofs on overloaded two-story structures, such as in the case of the Theological Seminary building pictured in Figure 25. Regardless, giwa roofs were continually used on two story Joseon-influenced structures throughout early modernization and into the colonial period.

Visual evidence suggests that, overall, Lee’s projects were typically designs modified from Joseon architecture, so much so that it has been theorized by Korean scholarship it was Lee’s first buildings that inspired the continued use of Joseon architecture in Presbyterian buildings throughout Korea’s early modern period.49 If nothing else, it can be said that he had a significant impact on the local built environment of Pyongyang. To be sure, he was involved in at least seven construction projects between 1900-1901 alone.50 Even a decade later, as Christian mission compounds were becoming increasingly Westernized and shifting towards more modern versions of American school architecture, Lee’s last known building project shows he continued to draw from Joseon architectural design before finally leaving Korea in 1912.

The modification of hanok and similar hybrid Korean structures became more sophisticated, more modern, over time. The specific kinds of structures discussed here, and those with turn-of-the-twentieth-century “Orientalist” characteristics, became less common, but they were still sometimes found in urban centers. The alteration of Joseon architecture continued in Korea’s rural interior, where the Japanese government commonly repurposed Joseon buildings as administrative offices after annexation had fully set in. Some Christian (protestant) mission stations were heavily reliant on the influence of Joseon architectural design for decades. This was particularly true for institutional structures, like churches and schools. Missionary residences, however, as a general trend, became less Korean as the peninsula modernized.

Throughout the colonial period, Joseon architectural design was appropriated by the Japanese in unusual examples, like train stations, and was adapted to city life by Korean builders in the 1920s with the advent of urban city hanok. Yet it was Western diplomats, the missionary community, and church congregations that first started adapting and modifying Joseon architecture, becoming responsible for a number of interesting hybrid structures in pre-colonial Korea. To this day, some of the most recognized extant fusions of early modern Western and Korean design are Christian religious structures, namely the well-known Ganghwa Anglican Cathedral (built 1900) and Nabawi Catholic Church (built 1906). How ever these buildings evolved over time, it can be said that modified Joseon architecture – renovated or newly built – was initially the result of Western influence. Dependent on local circumstance, this became one kind of physical manifestation of the cultural pluralism occurring in early modern Korea, setting the stage for later architectural experiments.

Footnotes and Citations

1 Note that this claim was also made of the Italian consular buildings, which were arguably built with more Chinese influence than Korean. Other than that, the original comments appear correct. See this essay on “compradoric” architecture for images of the Italian consulate and legation; William Franklin Sands, Undiplomatic Memories (New York: Whittlesey House, 1930), 98.

2 William Franklin Sands, Undiplomatic Memories (New York: Whittlesey House, 1930), 98.

3 North China Herald, June 29, 1888, p10.

4 George W. Gilmore, Korea From Its Capital: With A Chapter on Missions (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work, 1892), 268-269.

5 S. A. Moffett, Evangelistic Work in Pyeng Yang and Vicinity, October 1895. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection. Princeton Theological Seminary.

6 Though demand for Western-style brick can be partially attributed to the modification of Joseon buildings by Westerners, it should be noted that, while brick is almost categorically rejected as a “traditional” Korean building material, brick has been associated with Joseon yangban homes in a few early accounts. British consul William Richard Carles wrote in his 1888 account of Korea that one official’s home was “all built of brick”, while art and architecture historian Sekino Tadashi, whose conclusions were at times somewhat questionable, wrote that yangban homes were typically surrounded by brick walls. Sekino was probably referring to clay materials more akin to tile, like those used in Korean kkotdam, however the wording in Carles’ account could suggest the home was built of Western or Chinese brick. See William Richard Carles, Life in Korea (London: MacMillian and Co., 1888), 62; and Tadashi Sekino, “Chosen no jutaku kenchiku” [Joseon housing architecture], in Jutaku kenchiku [Housing architecture] (Tokyo: Kenchiku sekaisha, 1916), 156-163., as cited in Yoonchun Jung, “Inventing the Identity of Modern Korean Architecture, 1904-1929” PhD thesis, McGill University, 2014, 67.

7 Anabel Major Nisbet, Day In and Day Out in Korea (Richmond: Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1920), 35.; Perhaps the earliest mention of glass windows in foreigners’ renovated hanok goes back to the early 1890s, at which point the text may imply it was commonplace: “Foreigners in remodeling native houses for themselves use glass windows, but natives, like the Japanese, use translucent though not transparent white paper.” George W. Gilmore, Korea From Its Capital: With a Chapter on Missions (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School, 1892), 124. However, the importation of glass goes back to at least the end of 1879, when an American consular report showed Korea importing 1,327 yen worth of glass from Japan. Reports from the Consuls of the United States on the Commerce, Manufactures, Etc., of Their Consular Districts, No. 4 (Washington: Department of State, 1881), 237.; A different report for the year 1882 specifically claimed glass for windows being imported to both Busan and Wonsan. Commercial Reports Received at the Foreign Office From Her Majesty’s Consul-General in Corea (London: Harrison and Sons, 1884), 3.

8 The Korea Review, Vol. 1 (Seoul: Methodist Publishing House, 1901), 168.

9 Burton Holmes, Burton Holmes Travelogues, vol. 10 (New York: McClure Company, 1908), 56.

10 Mary V. Tingley Lawrence, A Diplomat’s Helpmate (San Francisco: H. S. Crocker Company, 1918), 8.

11 Korea Through Western Eyes, p.162. Note that according to Neff’s research, the painter also completed a mural in the parlor showing a naval scene. Neff also briefly discusses Rose Foote’s gardening at the legation in this section.

12 Mary V. Tingley Lawrence, A Diplomat’s Helpmate (San Francisco: H. S. Crocker Company, 1918), 9.

13 Mary V. Tingley Lawrence, A Diplomat’s Helpmate (San Francisco: H. S. Crocker Company, 1918), 9.

14 Horace Newton Allen, Things Korean (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1908), 67.

15 Foulk was an American naval officer who briefly served as acting chargé d’affaires to Korea twice. Foulk’s own photographs show doors with sections of glass inserted into hanok doors, like those found in the Church of the Advent and the American Mission. More specifically, it appears that there are reflections on the doors, suggesting glass had been inserted into them.

16 Helen Heard to Amy Heard Gray, December 4, 1891. From the transcribed letters of Amy Heard Gray, made available online by Robert M. Gray.

17 This kind of Russian stove was also, according to his own letters, built in the house of Eugene Bell in Mokpo.

18 This geometry is seen in buildings like Jipokjae (Gyeongbokgung), but also found in the woodwork of the thrones in buildings like Junghwajeon (Deoksugung).

19 See Dae Young Ryu, “Understanding Early American Missionaries in Korea (1884-1910): Capitalist Middle-Class Values and the Weber Thesis,” Archives de sciences sociales des religions [Online], January-March 2001, posted on August 19, 2009, accessed February 8, 2015.

20 Ernest F. G. Hatch, Far Eastern Impressions (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1905), 46. Also read Burton Holmes’ travelogue on Seoul for an understanding of his dislike of Joseon’s aesthetic disruption. Burton Holmes, Burton Holmes Travelogues, vol. 10 (New York: McClure Company, 1908).

21 It’s possible the same kind of heating stoves were used in the Underwoods’ first Jeong-dong home. “There were big fireplaces, too, in his house; the first one built in with his own hands.” Lillias H. Underwood, Underwood of Korea (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1918), 66.

22 Eugene Bell, letter to his mother, December 11, 1898. Presbyterian Historical Society. On Colonial Korea, this same quote was used in the 2016 photo essay regarding Mokpo.

23 Clara Hedberg Bruen, 40 Years in Korea, 137. Undated manuscript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

24 Letter from J. E. Adams, April 6, 1896. Korea Microfilm Index, Korea Letters – Vols. 1-2 (1884-1900). Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

25 Note that “Pyeng Yang” was one spelling variation of “Pyongyang”, and I have opted to use “Pyeng Yang” only when it is part of the name of a building or institution. Note that Pyeng Yang Central Church was also sometimes referred to as Pyeng Yang City Church in primary sources penned by missionaries at the time.

26 There is no evidence showing Lee had any professional engineering training, though he had some amount of practical knowledge, being able to get levels for foundations and assemble parts of buildings. Also, Lee claimed they (presumably the Presbyterian Mission) would not make contracts with Korean builders/laborers. This occurred during the construction of Pyeng Yang Central Church. Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, June 17, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

27 Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, May 27, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

28 Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, May 27, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

29 Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, May 27, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

30 Samuel A. Moffett, Report for 1899-1900. Loose three-page memorandum. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

31 Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, May 27, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

32 Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, May 27, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

33 Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, May 27, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

34 Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, May 27, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

35 Letter from William M. Baird to Dr. Ellinwood, June 30, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.; In June 1900, Graham Lee noted that Baird’s house was mostly completed, aside from the hardware. Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, June 17, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

36 Letter from William M. Baird to Dr. Ellinwood, November 27, 1900. Transcript.; Note that a different report from Baird states the Academy, as an institution as opposed to the building itself, opened on September 25. Samuel A. Moffett and Graham Lee, “Pyeng Yang City Church,” Annual Report of Pyeng Yang Station, For The Year 1900-1901, 24. William M. Baird Papers, Presbyterian Historical Society.

37 Letter from William M. Baird to Dr. Ellinwood, November 27, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

38 William M. Baird, “The Academy,” Annual Report of Pyeng Yang Station, For The Year 1900-1901, 29. Presbyterian Historical Society.

39 Samuel A. Moffett and Graham Lee, “Pyeng Yang City Church,” Annual Report of Pyeng Yang Station, For The Year 1900-1901, 5. William M. Baird Papers, Presbyterian Historical Society.

40 Report for 1900-1901 of the Pyeng Yang Station, Korean Presbyterian Mission, circa September 1901, 11. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection. Princeton Theological Seminary Library.

41 Samuel A. Moffett to Dr. Ellinwood, October 22, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

42 Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, May 27, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

43 A memorial written for Leck indicates that Lee left Korea in May 1901. In Memory of George Leck, 6. Fifty page printed memorial booklet with handwritten date “1901.02”. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.; Another source states Graham Lee went on furlough to the United States in June 1901. William M. Baird, “The Academy,” Annual Report of Pyeng Yang Station, For The Year 1900-1901, 29. William M. Baird Papers, Presbyterian Historical Society.

44 In Memory of George Leck, 7. Fifty page printed memorial booklet with handwritten date “1901.02”. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

45 William M. Baird, “The Academy,” Annual Report of Pyeng Yang Station, For The Year 1900-1901, 29. William M. Baird Papers, Presbyterian Historical Society.

46 Handwritten notes on mounted images of “The Whole Campus” and “Alexander Dormitory”. William M. Baird illustrations, 1905-1907, 1914-1916, n.d. William M. Baird Papers, Presbyterian Historical Society.

47 Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, May 27, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

48 Transcript of letter or report from 1901. Loose paper with missing title or letterhead in the second section of the Henry Munro Bruen documents. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.

49 See Chang-Won Chung’s 2004 “A Study on the Activity and its Influence of Pioneer Missionary in Korea Protestant Mission Architecture: Focused on the Architectural Activities of Graham Lee”.

50 In addition to the previously mentioned Pyeng Yang Central Church, Academy building, the Baird residence, and the Wells residence, Lee also reportedly worked on the women’s chapel (Marquis Chapel), the Hunt residence, and an unnamed children’s school building. Letter from Graham Lee to his parents, June 17, 1900. Transcript. Samuel H. Moffett Manuscript Collection, Princeton Theological Seminary.; Note that given the nature of missionary-led construction in Korea during this time, it is also possible that buildings like the Christian Book Store, Theological Seminary, and Grammar School were also Lee’s projects.

Dear Nate,

Another great post on an exciting topic!

I particularly enjoyed it, because – and this is purely coincidental – I recently discovered a book chapter that talks about the same phenomenon – although in a different light.

I’m visiting Taipei this September, so I was looking for some reading materials on the history of Taipei’s urban planning. During my search, I stumbled upon this book, which had an article on Imperial Japan’s urban management in its occupaied territories. Of course, Keijo is one of the cities that it pays a lot of attention to, and one chapter, in specific, looks into the creation of ‘Hyun-gwan’ as an example of the modernization of Han-ok during the occupation era.

I find the author’s take on the issue differs with yours to a certain degree, so I thought I could share it with you.

The book chapter is called:

Woo D (2014) On Park Kil-ryong’s Discovering, Understanding, and Desigining of Korean Architecture. In Kuroish I (ed.) Constructing the Colonized Land: Entwined Perspectives of East Asia around WW2. New York: Routledge, pp.193-214.

Best,

Byeong

PS.

If you don’t have an access to the book, just send me an email!

LikeLike

Hi Byeong,

Always good to hear from you. Hope you have a good time in Taipei, there’s lots to see there!

Constructing the Colonized Land is a text I frequently reference on the colonial period. It’s a great book and I’ve read the chapter on Park Gil-ryong.

One of the reasons I referred the buildings in my article as “modified hanok” instead of “modernized” is to show they were different than the city hanok and Park Gil-ryong’s ideas in the 1920s-1940s. This is something I don’t really get into in my article, but I did briefly touch on it in my conclusion.

The time periods were different. From 1883 to early 1910s, Westerners were modifying Korean buildings, making do with what they had, but there is hardly any evidence suggesting these Westerners were making new design ideas related to architectural theory like Park Gil-ryong was. It was more that a given Western missionary wanted a bay window in their hanok, and so had a carpenter add it on, or had central porches added to mimic their homes in America. It wasn’t a thoughtful, planned stylistic shift in the way that Park Gil-ryong’s was, who was exploring what a modern Korean home should be like. Early Westerners before this were just trying to improve their living spaces according to their own standards, not making judgements on how to modernize homes for Koreans. To a degree, any “modern” ideas for updating a home were arguably generally still rooted in Victorian era thought, not the “modern” scientific sterility of the 1920s that trended around the globe.

So, you have two distinct periods of change in hanok. The first from 1883-1910 being a sort of haphazard, unplanned one led by Western missionaries and diplomats. The second from 1920s-1940s being more theoretical and planned by trained architects and builders. The period from 1910-1920 needs more exploration as I’d say it’s unclear what connections there are between 1920-1940s modern city hanok and earlier modified hanok. It’s also important to note that Park Gil-ryong had a lot of ideas, but few of his modern ideas were used in the typical Korean home – evidence points to mostly upper class having “modern hanok”.

In summary, I think the author, Woo, is accurate in his assessment, though the 1914 Gyungwon-dang building sits in that transitional period and needs to be reconsidered. His article is a wonderful resource for understanding how some thinkers wanted the Korean home to change in the 1920s-1940s.

It’s important to remember that Korea changed a lot between the 1880s and 1940s, and so what was happening with “modified hanok” from 1880s to 1910 was distinct from what happened with “modern hanok” or “city hanok” between the 1920s-1940s. How the two are related, if they are related at all, is a big question I have!

LikeLike

I’ll make one more comment since I mostly talked about houses. If you consider intent, even the public buildings (churches, schools) built by Western missionaries that used Korean design were done so because the Christian community was concerned with optics and winning converts. Letters within the Presbyterian community show some discussion of this. As time went on, Western missionaries increasingly abandoned Korean design in the mid to late 1910s as the peninsula gradually accepted more modern ideas (there is some evidence indicating this began as early as the late 1900s). In my estimate, this helps to suggest they weren’t concerned with creating an architectural movement, but were largely using architecture as a means to a religious end. This probably varied to some degree, but the fact that these non-architects were able to have such buildings constructed at all is somewhat amazing to me.

LikeLike

Right.

The distinction between those two seems to be very crucial.

Also an insighful note on the use of Korean design by Western missionaries!

Thanks for the thoughtful reply.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Life and Times of Harry Chang: Builders in Early Modern Korea (1880s-1910s) – Colonial Korea

Pingback: Chosen Christian College (1910s-1950s) – Colonial Korea

Pingback: The Architecture of Henry Bauld Gordon in Korea (1899-1905) – Colonial Korea

Pingback: Cultural, Practical, and Regulatory Influences on Early Modern Building Typologies and Floor Plans (1880s-1910s) – Colonial Korea

I’m enjoying seeing your posts everyday! Looking forward to seeing a new interesting post 🙂

LikeLike