Before the rise of reinforced concrete, brick was the heart and soul of many an early modern building in Korea. Red brick architecture arrived in the 19th century, with some of the earliest (non-palace) examples being the Busan Japanese Administration Office in 1879, the Sechang Trading Company in 1884, the Beonsachang Armory in Seoul (1884-present),1 and Henry Appenzeller’s Paichai Academy building (Baejaehakdang, 1887-1932). In those early days, some of these brick materials were imported. By the time of Myeongdong Cathedral’s construction, brick demand was increasing, with the Yaghyun Parish and the British Legation having already been completed in 1892. The outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War (1894) halted brick imports, leading the masonry supervisor working with Eugene Jean Georges Coste, the priest in charge of construction, to start producing bricks domestically to meet the cathedral’s demands.2 Years later, in tandem with growing concern over fireproofing the Japanese empire’s urban centers, the Resident-General supported the construction of a brick factory in October 1907.3

Yet domestic brick production seems to go back decades earlier. In Gyeongbokgung, royal buildings from the late 1800s were sometimes, under Chinese influence, implementing red and black brick. It’s unclear whether or not these were imported, but it is worth noting that there were Joseon government agencies, having been reorganized in 1882, that existed specifically to oversee giwa and brick production.4 Documents on craftsman production techniques, such as kiln firing bricks, were made earlier in the Joseon period,5 though brick in its modern form doesn’t seem to have started to appear until the time of the construction of the Amisan chimneys (Gyeongbokgung), around 1870, and the opening of Korea to foreign trade, in 1876.

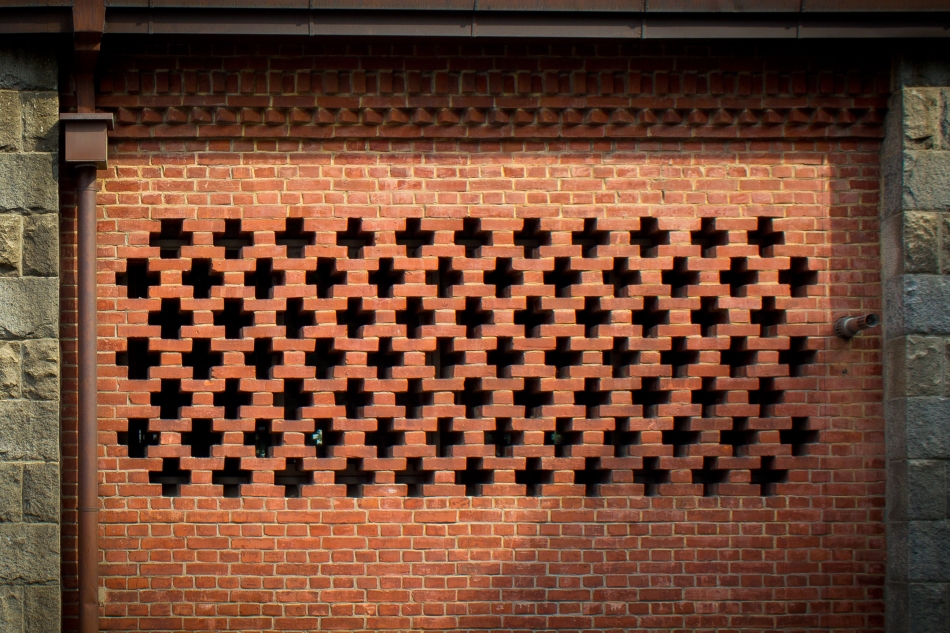

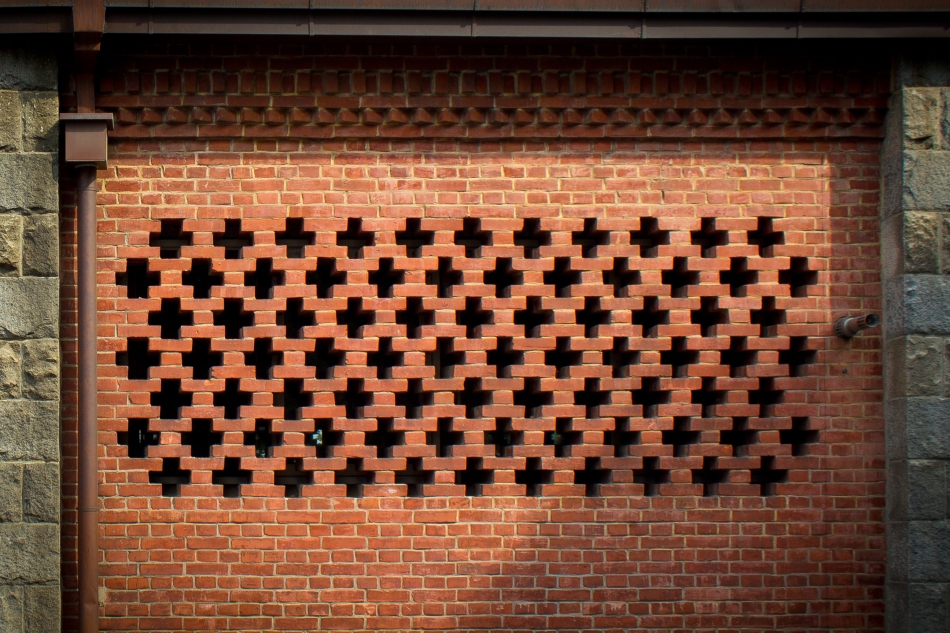

The Resident-General reported the import of nearly four millions bricks into Korea between 1908-1910,6 with 36 different brickyards established in Korea by 1915.7 As brick architecture was normalized through its use in everything from port facilities and commercial spaces to homes and governments offices, so a particular trend appeared: perforated brick walls. It specifically, though not always, showed itself as a cross shaped design.

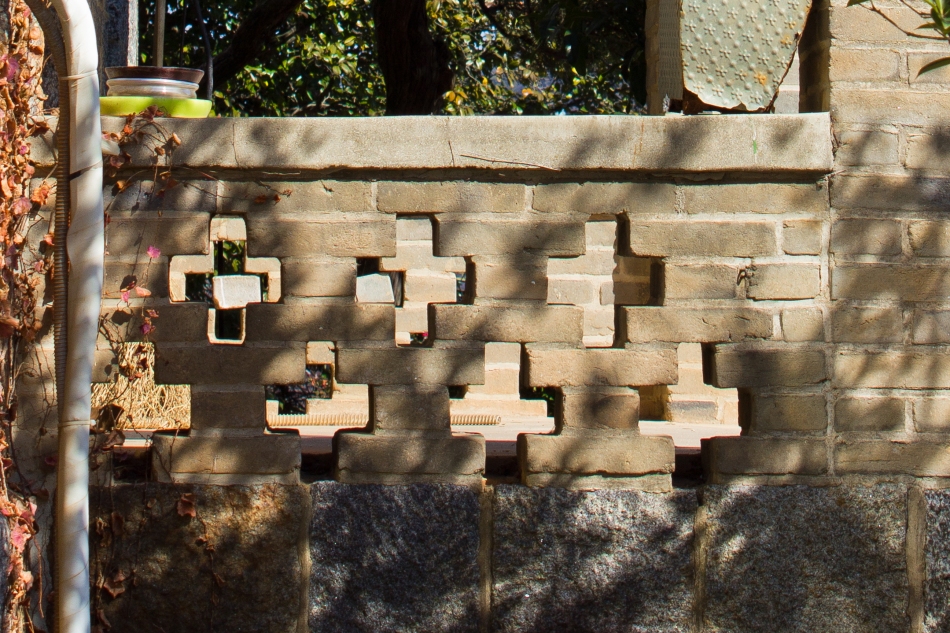

Perforated brick, from a practical standpoint, was a compromise between privacy and environmental control. By leaving holes in the wall, air could move through, for example, a courtyard, while still making it difficult for casual passers-by to see into the property. In dense urban settings, this theoretically could alleviate the changes in microclimates created by gridded streets and new buildings that redirected wind patterns. Aesthetically, perforated brick helps to break up an otherwise plain wall or facade. In most cases, it was cosmetic and superficial, meant to add to the visual quality of the building.

How this cruciform pattern first arrived in Korea is unclear. We know that perforated surfaces in general are not at all unique to Korea, but are used throughout the world – particularly in the ornate, geometric designs of Middle Eastern, Indian, and north African architecture. Regarding the examples in Korea, one could conjecture that the perforated cross design was learned at a Japanese university under the study of an early Western advisor like Josiah Conder – the father of Japanese modern architecture.8 If not learned there, it may have merely been copied from any number of other Europeans in the late 19th century. Japanese architects then could have worked it into their buildings across the empire.

In this way, from a Western-Christian perspective, it would be easy to assume that the cruciform pattern came from the West. It’s a design that perhaps conjures up images of Europe’s old world countrysides, rural towns, gardens, estates, and churches. To be sure, it was used in quite a few missionary and religious buildings in Korea.

However, the issue with this theory is that perforated brick doesn’t actually appear to have been that common in European and American urban centers, instead being found in, for example, melting-pot areas with Moorish and Byzantine influence like southern Spain and Italy. Some examples of buildings in Europe with perforated brick are built in non-Western styles, such as the old Byzantine influenced granary (1869) on the River Avon in Bristol, U.K. (unpictured). Josiah Conder himself designed and built at least one Indo-Saracenic Revival style building in Tokyo: the National Museum of Japan (unpictured). Yet even in these examples, where one might expect to find such a design, this specific cross pattern does not appear.

With few cases of perforated brick found in the West, it is unlikely that Western-trained Japanese architects were the ones pushing for the spread of the cross pattern. And even as Japanese architects did, from the 1920s on, make use of Middle Eastern and Indian (revivalist) styles in some of their modern buildings, this specific perforated cross pattern does not seem to have been common in early modern Japan either. A more likely explanation for the origins of the perforated cruciform design then lies not in the educated architects of Japan, nor in the Westerners that imported their building styles into Asia, but in the vernacular architecture of particular areas of China.

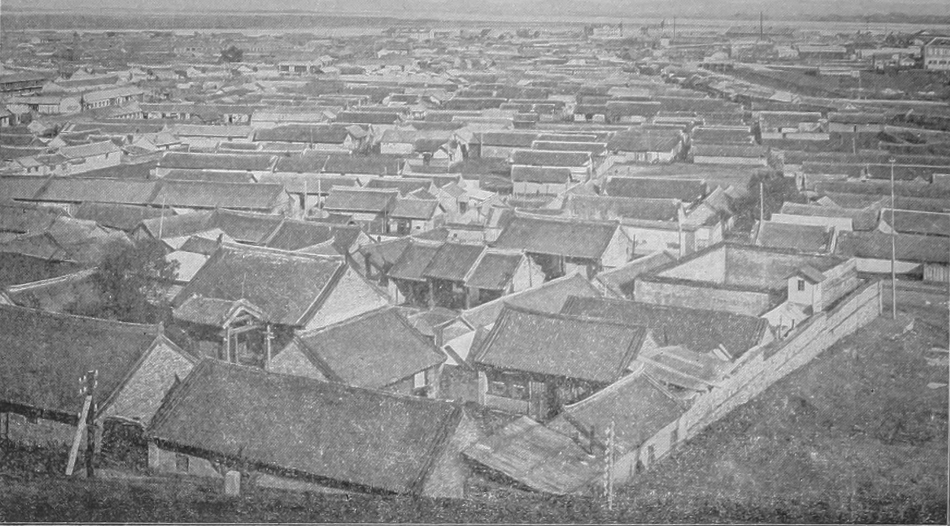

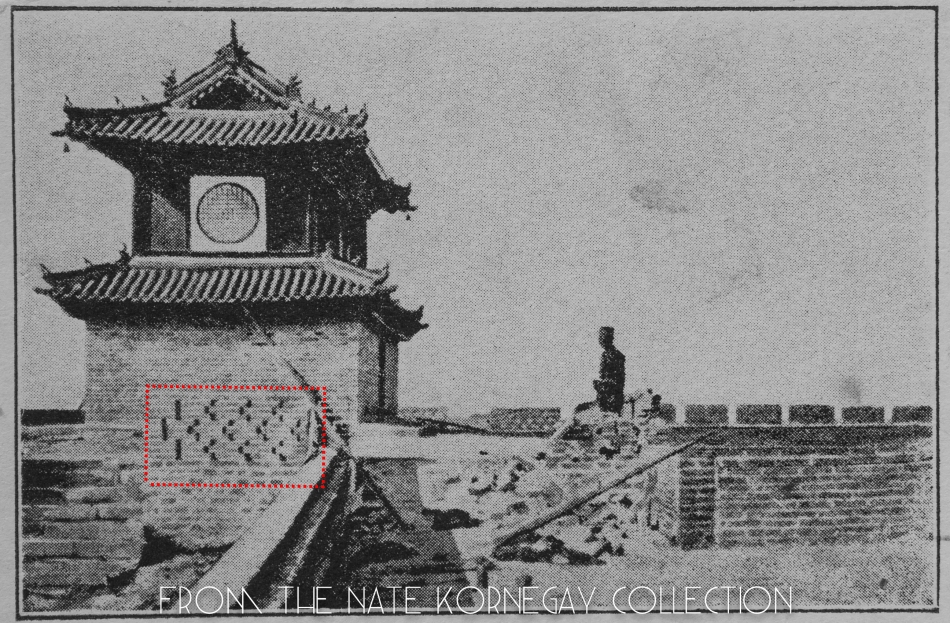

In Shanxi, a landlocked Chinese province roughly the size of South Korea, city blocks of old Qing era siheyuan courtyard houses still remain. Now promoted as tourist hot spots, these homes of Jin merchants commonly featured perforated brick designs, including the aforementioned cross pattern. The design is such an important part of Shanxi architecture that it is even found in the rural yaodong cave houses of the same province, which have been continually added to and occupied for centuries.

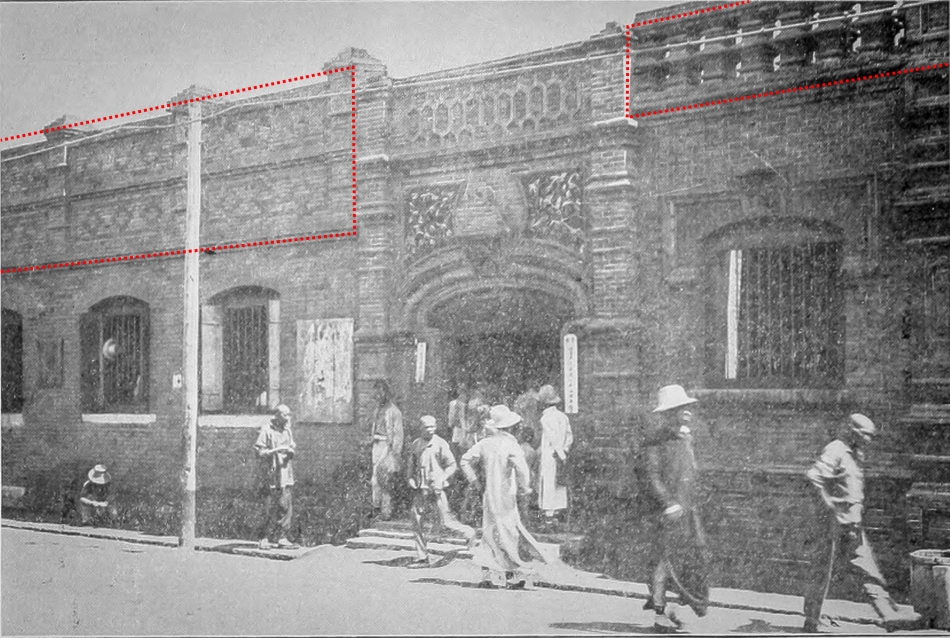

This perforated cross design, and perforated brick in general, was entirely absent from Korea until its opening to trade and the arrival of (relatively) free Chinese merchants. As thousands of Chinese soldiers marched into Korea in the 1880s, it’s been said that Qing merchants took advantage of the situation in order to make inroads into the peninsula. As Korea continued to open to foreign influence, Chinese settled down and developed their own businesses. At the time, the foreign population in general was not large at all. But by 1893, despite fierce competition with other foreign business, Chinese merchants were importing 49% of all goods brought into Korea.9 Qing businessmen and company agents were truly spread throughout the peninsula, from major urban centers like Seoul all the way to small river ports like Yulpo (Jeollanamdo).10

There were then those Chinese that got into the business of construction, like Jiang Francisco, the foreman in charge of the brick work at Jeondeong Cathedral in Jeonju (completed in 1914).11 The fact that many early masons in Korea were from China further supports the theory of perforated brick originating in the center of the Qing Empire. Indeed, the very rectory of Jeondeong Cathedral built by Chinese masons makes heavy use of this perforated cruciform pattern in its balcony and porch walls.

The influence of Chinese merchants, and of Chinese masons, at the turn of the 20th century should not be underestimated. Trade relations and the movement of people between the Qing and Russian empires could also explain why, way over on the frontier of Vladivostok, the same cross design can be seen in the perforated brick facades of downtown Neo-Classical style buildings.

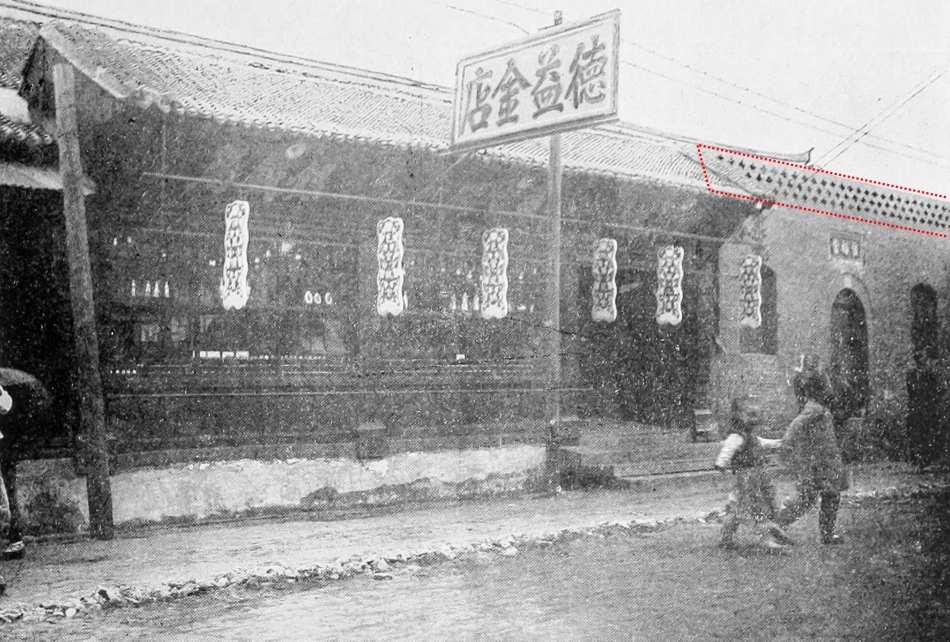

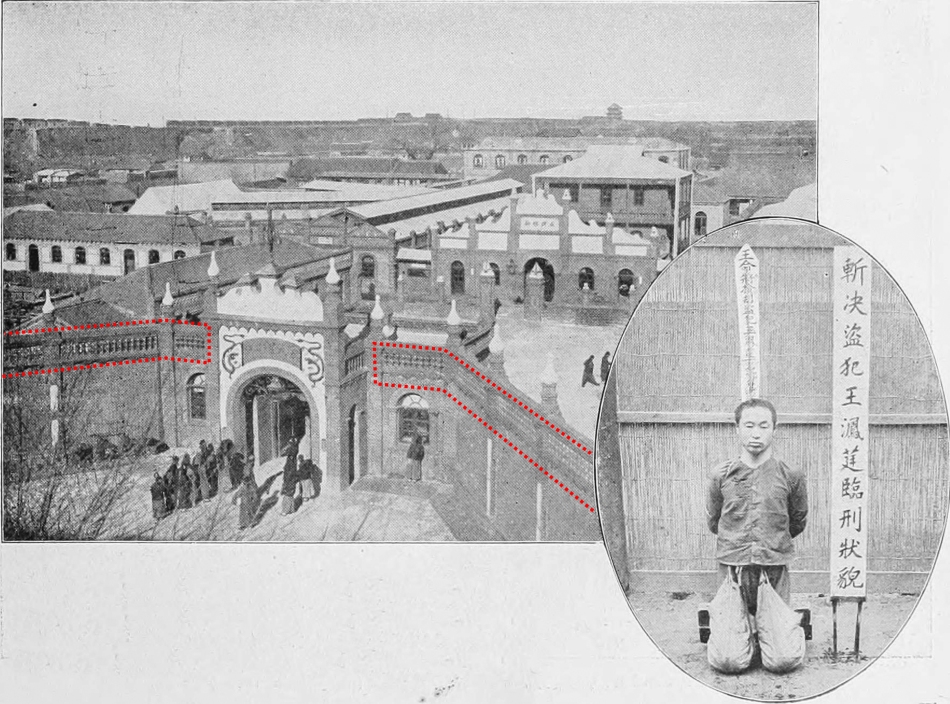

Jin (Shanxi) merchants were known to have branched out into other countries by the end of the Qing era, taking their trade to Mongolia, Russia, and northern Korea. However, it is unclear whether they specifically made it further south to places like Seoul. We know that Jin businessmen mostly stayed within China’s interior, sometimes dealing with the imperial court, eventually going into modern banking. To then say that the perforated Qing cross design came directly from a merchant group that was internally focused would be questionable. In fact, it is difficult to say with certainty which part of China this kind of brick design first originated. Yet it is likely that this design was brought to Korea, as a part of cultural diffusion, from places like Shenyang (old Mukden) – a city through which many Chinese merchants have passed for centuries on their way to Korea. In addition to its own courtyard homes, Shenyang’s many institutional structures contained this same cross design.

After the arrival of Chinese settlers, perforated brickwork became widespread in Korea, having been found in buildings from Pyeongyang to Busan. This very simple, even mundane, Qing design broke cultural barriers and architectural styles, making its way from churches and commercial buildings to Japanese made homes and hanok as well. The design also spanned several decades, having been found in structures built between the late 1880s and late 1930s (there is evidence of it being used into industrialization, suggesting either a resurgence or continual use of the design). During a time of intensely rapid architectural change in which building trends would shift within just a few years, the staying power of the perforated cross is noteworthy. This is despite the fact that the Qing cross design might have been left out of the colonial Japanese architectural world. That is to say, there are few clear cases of the design being used in institutional, non-residential structures that were likely designed by Japanese architects.

The key to its long-lasting implementation was likely due to a number of things. First, the geometry of the cross shape is so generic, so simple, that it arguably does not conflict with the vernacular architecture of any culture. It can be worked into many styles, kept in either its basic form or elaborated on according to a particular architectural type. Secondly, China had long been known for its masonry and brickwork. As foreigners began calling for Western styled buildings, Chinese masons and laborers seem to have been some of the few available in Korea. Lastly, the earliest Japanese settlers – who were not infrequently at odds with each other, various foreign settlers, the Korean government, and even the Japanese government itself – were largely disorganized for a time.12 This disorganization may have been one of the reasons Chinese merchants faired so well, allowing for masons to establish a foothold in Korea, thus resulting in the Qing cross finding its way into a number of early modern brick structures.

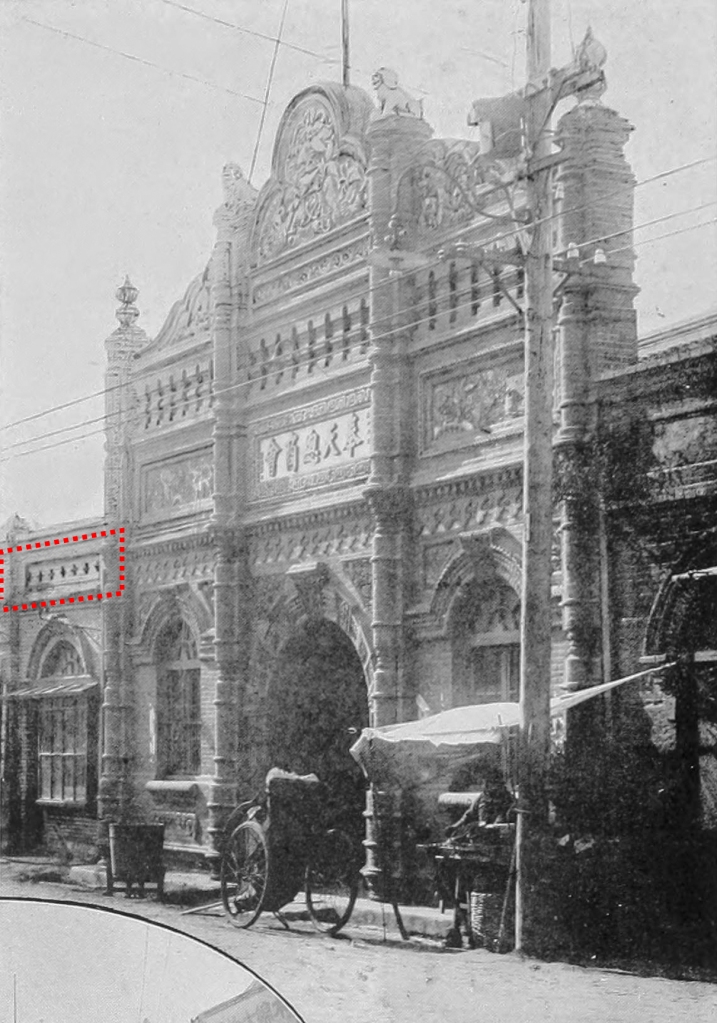

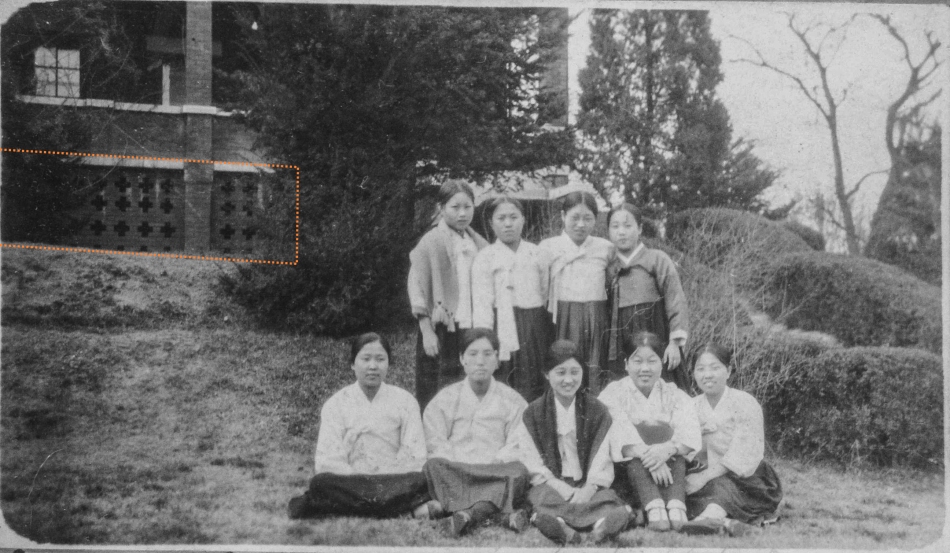

The earliest known example of this cross design appears to have been used above the top string course in one of the Paichai Academy buildings (1887-1932, pictured below). Christian missionaries relied heavily on Chinese labor in the construction of their homes, churches, and medical facilities, favoring them as workers over other people groups due to their perceived strong work ethic.13 This means that the Qing cross was commonly featured in Christian operated schools, like a building on the campus of Ewha, photographed around 1938 (pictured below).

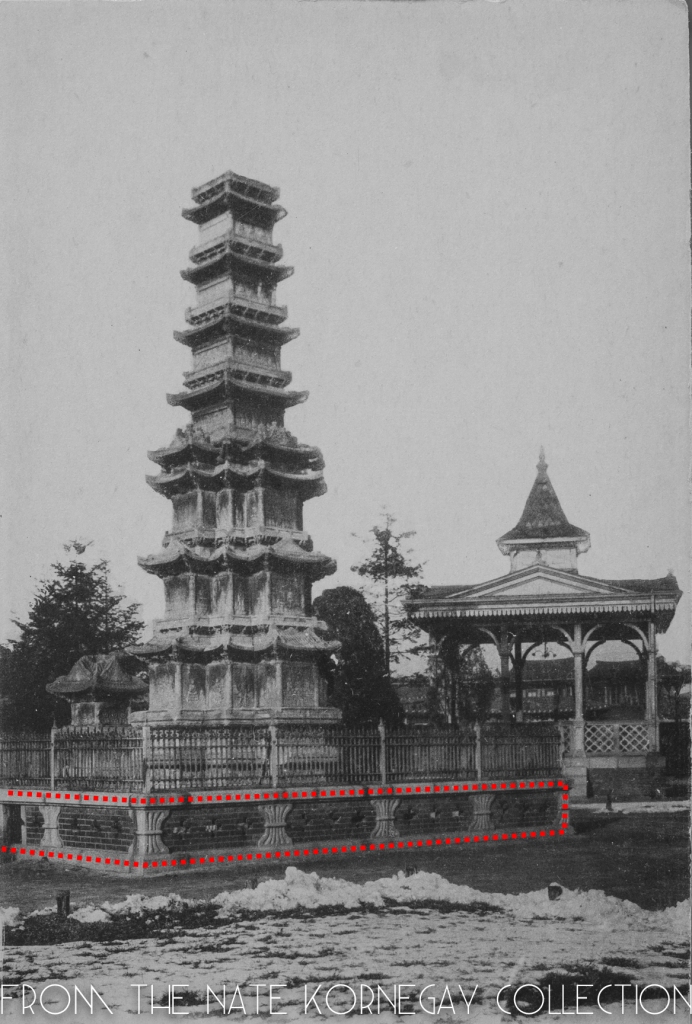

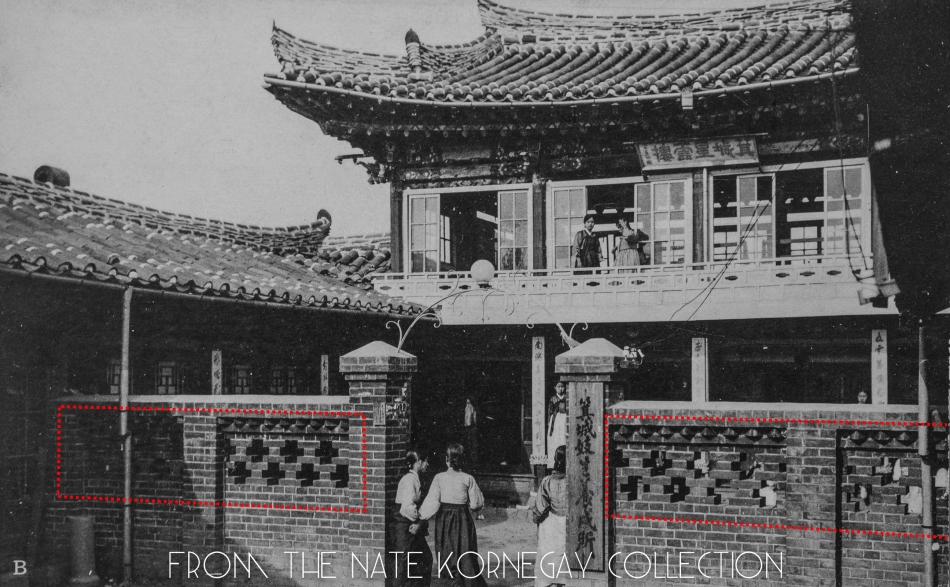

In a few seemingly rarer cases, it was institutionally adopted by non-Westerners. The stone fencing surrounding Wongaksa Pagoda in Seoul’s first modern public park, Tapgol Park, had the Qing cruciform pattern added to it in the early to mid 1910s.** In Pyeongyang, the gisaeng school clearly made use of Chinese style brickwork in its walls. Chinese architecture seems to have been mixed with Japanese temple design in the building of Deokhwangwaneumsa (덕환관음사), a Japanese Buddhist temple in the planned city of Jinhae. Japanese wood joints were used for the roof framing, but the ornamentation is rather Chinese. The temple not only made use of the perforated Qing cross in its brickwork, but the same cruciform pattern is copied in the structure’s decorative woodwork (pictured below; a more recent photo can be seen on a blog by clicking here. The temple was demolished around 2012).

Unfortunately, none of these examples remain today. Yet we can still find perforated Qing cross patterns in at least thirteen remaining buildings in Korea today. A former Chinese draper’s shop in Jeonju perfectly models early modern Qing brick buildings, following the form of the previously pictured buildings in Shenyang (Mukden). Naedong Anglican Church, an institution that traces its heritage back to St. Michael’s Church of 1891, still exists as a good example of the perforated Qing cruciform in old Chemulpo (Incheon). Making heavy use of the design, the entire exterior wall of the church features this pattern.

Transcending culture, the perforated Qing cross was worked into many kinds of Western buildings, including the increasingly well-known former home of Albert Wilder Taylor, features the cross pattern in its porch. Other Westerners, particularly missionaries, made use of the Qing cruciform in their brick buildings as well (pictured below). The design continued to find use in hanok architecture, including the former Yi Jang-u house in Gwangju, the boundary wall of the hanok building attached to the former Yun Deok-yeong estate, and a large early modern hanok that previously sat on a retaining wall in Jangchung-dong (unpictured).

Chinese style brickwork then appears in some seemingly unlikely places. Ganggyeong, a former river port town and commercial center between Jeonju and Gunsan, made use of the perforated Qing cross in the entry building at its waterworks and reservoir. With evidence of Chinese settlers living here, and merchants passing through here, this example is not particularly unusual. However, in Gampo, a tiny fishing village developed by migrant Japanese fishermen on Korea’s east coast, red and black brick sit atop what is thought to have been an old iced warehouse. Resting a few meters from the site of the community’s demolished Shinto shrine, these bricks are a curiosity amidst the town’s remaining Japanese houses and businesses. Though we can hardly tell today, Gampo did have a small Chinese population during the colonial period,** offering further evidence of a significant, but forgotten, influence in Korea.

As engineers and construction workers, Chinese settlers left a distinct mark on Korea’s early modern cityscapes in big and small ways. Their work, in the form of Christian churches and schools, made tremendous impressions on visitors and locals alike, so much so that Japanese tourism media had to acknowledge the beauty of Myeongdong Cathedral despite the Japanese government’s many issues with Christianity in Korea. However, when it comes to the perforated Qing cross design, it is unclear whether or not some of the previously mentioned examples were directly built by Chinese masons and bricklayers. During a time in which quite a bit of architectural copying was occurring, there were plenty of opportunities for non-Chinese to appropriate such a brick design. This probably was occurring in examples constructed after the Korean War, but with regard to the colonial period, we simply do not know without more information.

In any case, the widespread existence of the perforated Qing cross, and of black and red brick in general, show that Chinese style masonry was influential in Korea’s early modern architectural sphere, informing the design of many buildings for at least half a century. On one hand, the perforated Qing cross arguably had a very real impact on the way people experienced the constructed world around them. Early modern hanok with perforated brick crosses are aesthetically different from those only made from wood. The black and red style of Chinese brick similarly played a significant role in altering traditional Joseon landscapes and added something different to Joseon palaces in the late 1800s. Furthermore, the numerous examples of the perforated Qing cross could suggest a significant amount of control, on the part of the Chinese masons, over each structure’s final design. On the other hand, to some of the local Korean populace, this perforated brick design may have merely been one more unfamiliar visual element in an increasingly strange sea of seemingly random foreign buildings. The perforated Qing cross was then simultaneously socio-historically significant and architecturally mundane.

Compared to the rest of the world, Korea’s engagement with modern red brick was relatively short lived, only getting about fifty years of popular use before reinforced concrete came into vogue. Brick buildings continued to be constructed into the industrialization of the 1960s, eventually only being used to finish facades as concrete became the vernacular South Korean construction material. However, brick was already losing some popularity as a structural material towards the end of Japan’s rule over the peninsula (though there were still plenty of architects using it). Perforated brick designs became rarer after industrialization occurred, yet the inverted, unperforated diamond-like form of this design (as seen in the previous image of Mukden Provincial Bank) actually lived on in the ceramic tiles of the 1960s-1970s, which were added to all kinds of buildings constructed between the colonial and industrialization periods. And while it is unclear precisely how the perforated brick cross design came to the Korean peninsula, it is fascinating to think that it was Chinese masons that left a little piece of Qing architecture all over Korea – in the schools, businesses, homes, public works, and churches of a modernizing land.

This article is the first in the series, Reading and Understanding Early Modern Architecture in Korea. It seeks to help both the scholar and general public in deconstructing and contextualizing specific aspects of early modern architecture in Korea. If this article has helped you, if you see a point that you’d like to discuss, or if you would like to collaborate on a project, please feel free to comment below or send a private message via the contact form.

Footnotes and Citations

1Cho Hong-Seok and Kim Chung-Dong, “A Study on the Formation of the ‘Jeokbyeokdol (Red brick)’ in Modern Korea,” Journal of Architectural Institute of Korea, Vol.19 No.9 (December 2010), 105.

2Cho Hong-Seok and Kim Chung-Dong, “A Study on the Formation of the ‘Jeokbyeokdol (Red brick)’ in Modern Korea,” Journal of Architectural Institute of Korea, Vol.19 No.9 (December 2010), 105.

3Cho Hong-Seok and Kim Chung-Dong, “A Study on the Formation of the ‘Jeokbyeokdol (Red brick)’ in Modern Korea,” Journal of Architectural Institute of Korea, Vol.19 No.9 (December 2010), 104.

4Cho Hong-Seok and Kim Chung-Dong, “A Study on the Formation of the ‘Jeokbyeokdol (Red brick)’ in Modern Korea,” Journal of Architectural Institute of Korea, Vol.19 No.9 (December 2010), 106.

5Cho Hong-Seok and Kim Chung-Dong, “A Study on the Formation of the ‘Jeokbyeokdol (Red brick)’ in Modern Korea,” Journal of Architectural Institute of Korea, Vol.19 No.9 (December 2010), 104.

6Cho Hong-Seok and Kim Chung-Dong, “A Study on the Formation of the ‘Jeokbyeokdol (Red brick)’ in Modern Korea,” Journal of Architectural Institute of Korea, Vol.19 No.9 (December 2010), 105.

7Cho Hong-Seok and Kim Chung-Dong, “A Study on the Formation of the ‘Jeokbyeokdol (Red brick)’ in Modern Korea,” Journal of Architectural Institute of Korea, Vol.19 No.9 (December 2010), 109.

8See Toshio Watanabe’s Japanese Imperial Architecture in section twelve of Challenging Past And Present: The Metamorphosis of Nineteenth-Century Japanese Art.

9Ryota Ishikawa, “Commercial Activities of Chinese Merchants in the Late Nineteenth Century Korea,” International Journal of Korean History, Vol.13 (Feb. 2009), 76.

10Ryota Ishikawa, “Commercial Activities of Chinese Merchants in the Late Nineteenth Century Korea,” International Journal of Korean History, Vol.13 (Feb. 2009), 83.

11Kim Chung-dong, “Jeondong Cathedral: Lovely Church at Home in a Village of Traditional Houses,” Koreana, Autumn Issue (2013).

12See Jun Uchida’s section on The World of Settlers in her book, Brokers of Empire: Japanese Settler Colonialism in Korea, 1876-1945.

13Numerous primary sources of Western Christian missionaries from Korea’s early modern period show that, in general, they found Chinese laborers to be better than Korean laborers, in their opinions.

*Thanks to JiHoon Suk for first introducing me to the remaining brick sewer, the Chinese restaurant, and the Yun Deok-yeong hanok in Seoul.

**Edits or additional information provided by JiHoon Suk after the article was published.

Pingback: The Chosun Hotel – Colonial Korea

Pingback: The Compradoric Style: Chinese Architectural Influence on Early Modern Korea – Colonial Korea

Pingback: Bricks in Korea | thesememorieswhich